Catching Up on the Housing Market

Homebuilders continue to outperform

Take a look at the best-performing S&P 500 sub-industries over the last year, and you won’t be surprised by who tops the list. The NVIDIA-led Semiconductors have surged by more than 100% since last February. You probably won’t be surprised to see Meta’s Interactive Media & Services sub-industry coming in at #2, either. That group has gained 90%.

But the #3 sub-industry over the last 12 months? That one you probably won’t see coming. It’s the Homebuilders.

A couple of years ago that knowledge wouldn’t have come as a surprise at all. We were in the midst of the hottest housing market since the mid-2000s, with home prices rising at 20% per year and mortgage rates at record lows. Today, mortgage rates are near 7%, on par with the highest we’ve seen over the last 2 decades, and real estate values have stalled. Yet the homebuilders continue to chug along.

Let’s dive a little deeper.

Nothing impacts affordability of housing quite like interest rates do. Few - if any - of us are going out and paying for our homes in full. Instead, we’re spreading our payments out over 30 years, with the bulk of the cost over those years going towards interest. Just a few short years ago, mortgage rates were at their lows levels on record. At less than 3%, US homebuyers could finance their homes for less than what the US Government borrows for today.

Fast forward to 2024, and the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate is roughly 7%. Even if home prices were unchanged over that period (and they weren’t), the increase in interest costs would mean a jump of 60% in the monthly mortgage payment.

That, along with the surge in home prices, has severely curbed affordability. Mortgage rates and home prices don’t exist in a vacuum - incomes have risen significantly over the past few years, too - but even when we normalize the data to account for wage gains, affordability over the past 2 years is as low as it’s been at any time over the last 30 years.

So why hasn’t the affordability crisis caused homebuilding stocks to crater? For one, because the US housing market is suffering from a severe, structural supply shortage. In healthy environments of years past, the months supply of existing homes available for sale averaged about 4.5 months. During the post-COVID housing boom, surging demand and supply chain disruptions drove that measure of supply to record lows. Demand may have cooled some since then, but inventories haven’t really recovered – there’s still only 3 months of supply available.

There’s good reason to believe the supply of existing homes for sales won’t improve any time soon, either. Millions of homeowners locked in ultra-low mortgage rates through pandemic-era refinances or recent relocations. It’s difficult for them to move if their new monthly home payment will be double or even triple their current rate.

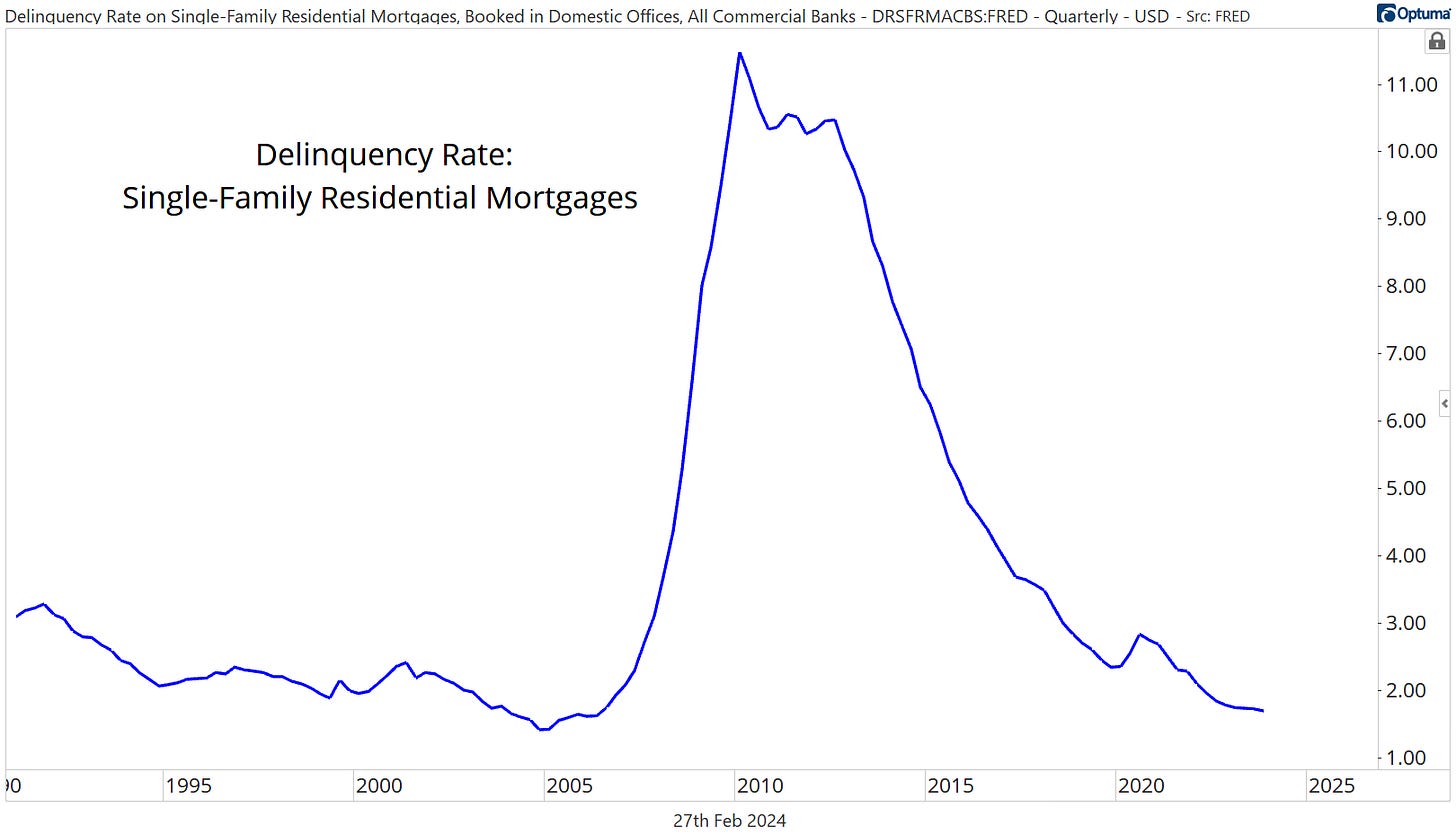

What about forced supply from foreclosures? Don’t count on that either. Delinquency rates on mortgages haven’t shown signs of material stress.

What about homes being ‘hoarded’ by investors or the ultra-rich, like the folks on Twitter keep telling us? That won’t solve it either. Vacancy rates (the percentage of all vacant houses including second homes and seasonal units) have been declining for more than a decade. Of homes that are available for rent, vacancy rates are still lower than the two decades prior to 2020.

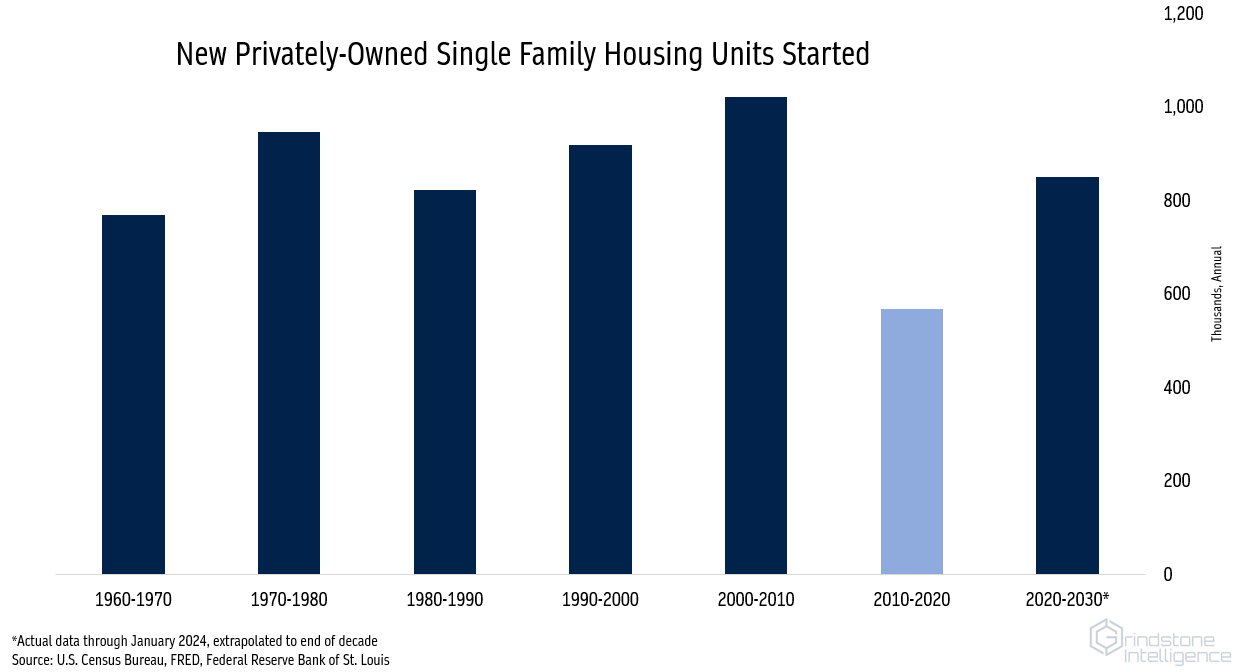

The simple truth is, we haven’t built enough homes in the United States over the last 15 years. Check out single family housing starts since the 1970s. From 2007 to 2019, starts ran below the 60-year average, even though the US population today is 75% larger than it was in the 1960s.

Here’s another way to visualize that shortfall. We’re on pace to return to average in the 2020s, but there’s still a huge gap to fill from the 2010s.

But housing supply isn’t something you turn back on with the flip of a switch. After the housing bust of the mid-2000s, builders and their suppliers were brought to the brink of destruction. Many of them went belly up, and the ones that survived did so by cutting back on risk.

Gone are the days of acquiring years and years of land supply and churning out as many homes as possible. Now, most of builders control land through options, but don’t actually own them. And fewer speculative homes are built, meaning more often than not, builders are waiting until a buyer is found before starting construction.

Even with their newfound discipline, it might seem that new home supplies are plentiful. The months supply of new houses is well above long-term averages and at levels that historically was consistent with economic recession. The housing market doesn’t look so tight now, does it?

It’s just an illusion.

The inventory of completed homes for sale isn’t elevated at all. The expansion has been entirely due to a rise in the number of new homes under construction. And the builders haven’t had any problem selling those homes as they reach the completion stage.

So the homebuilders are benefiting from a structural supply shortage in the industry, one that will take years and years to correct. They have another distinct advantage: the ability to alter their product to meet changing conditions.

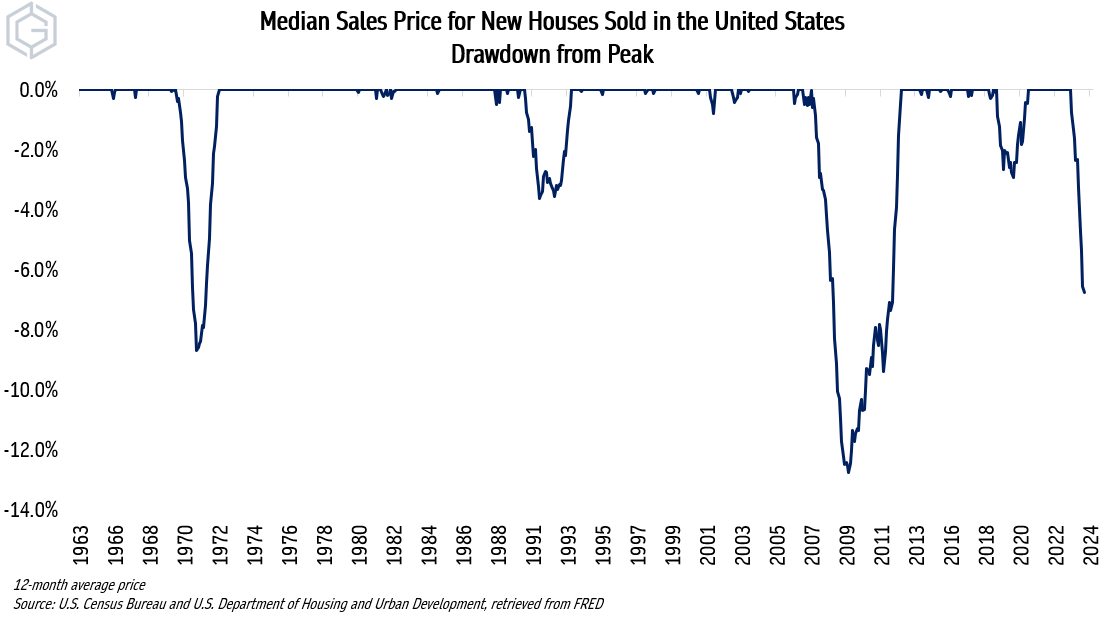

Check out the median sales price for new homes sold in the US. We’re 7% below the peak set last spring. If you didn’t know better, you’d think housing was in the midst of one of the worst collapses of the last half century!

Here’s an exchange from the most recent D.R. Horton earnings call to help explain what’s going on:

Q: “Is there anything else that buyers have been kind of responsive to, as far as like the levers you have, to kind of make payments work for them, or has there been a type - any sort of change to those strategies?”

Michael Murray, Executive VP and Chief Operating Officer, D.R. Horton: “Product selection. Generally, they’ll buy a smaller home to make the payment work and sometimes that’s within an existing neighborhood or moving to a different neighborhood that’s offering a smaller set of plans.”

Jessica Hansen, Senior VP, Investor Relations, D.R. Horton: “So our square footage was down again about 3% year-over-year. It was relatively flat sequentially, but we would expect just continued gradual moves down from a mix-shift perspective in terms of average square footage.”

The price of existing homes tends to be pretty stable, because the product itself doesn’t change. But new homes can change. You can adjust the floorplan or the finish of kitchen appliances. Or the countertops. Or the siding. Or any number of things to meet the requirements of current demand. Despite the decline in prices, gross margins for the industry today are still higher than they were at any time in the decade prior to COVID.

What homebuilders can’t change are mortgage rates.

Oh wait, they can do that, too. Here’s a clip from the Q3 call.

Paul Romanowski, Chief Executive Officer, D.R Horton: “We tend to stay about 1 point to 1.25 points below market at any given time, and today, we’re offering on FHA government loans roughly in the 5.99 rate, and on a conventional 6.25, which is right in that range of 1 point, 1.25 points below today.

“About 60% of our total closing are used with some form of a rate buydown.”

Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised by the Homies are coming out of a big base on their own and relative to the rest of the market.

Until next time.