Help Wanted: The U.S. Labor Market Continues to Tighten

I just got back from vacation. It’s the first true vacation my wife and I have taken with our daughters, and I’m happy to report that we survived. Between a few road trip meltdowns and theme park tantrums, we even managed to have a little fun.

Smoky Mountain National Park is beautiful in the fall. The terrain isn’t nearly as rough as what you’ll find in the Rockies, so it’s great for hiking with the kids. Especially if you’re carrying them on your back (shout out to my awesome wife for rocking the trek up to Grotto Falls).

We also spent some time in Gatlinburg, Tennessee. From the looks of things out there, pandemic fears aren’t hurting tourism demand anymore. The bigger problem is a staffing shortage. “Now Hiring” advertisements blanketed nearly every window on the Parkway shopping strip and in the surrounding area.

My anecdotal experience is overwhelmingly confirmed by available labor market data. The U.S. unemployment rate skyrocketed to 14.8%, the highest since the Great Depression, during the peak of the COVID crisis. It’s fallen almost as quickly. At 4.8%, the U-3 rate is already well below the long-term average.

For the 7.5 million people still looking for work, ample opportunities are available. The most recent estimate of job openings exceeded 10 million. That comes to 1.25 job openings for every job seeker – the highest number ever recorded.

And while rising energy costs and supply chain issues have dominated the financial news cycle of late, if you ask business owners about the biggest problem they face, labor quality far outstrips inflation concerns.

Half of all employers in the August NFIB survey reported job openings they couldn’t fill during the month. Of those with active job openings in August, 91% said there were few or no qualified applicants for the position they were trying to fill. The number of hirers reporting zero qualified applicants for a job posting was the highest in 48 years.

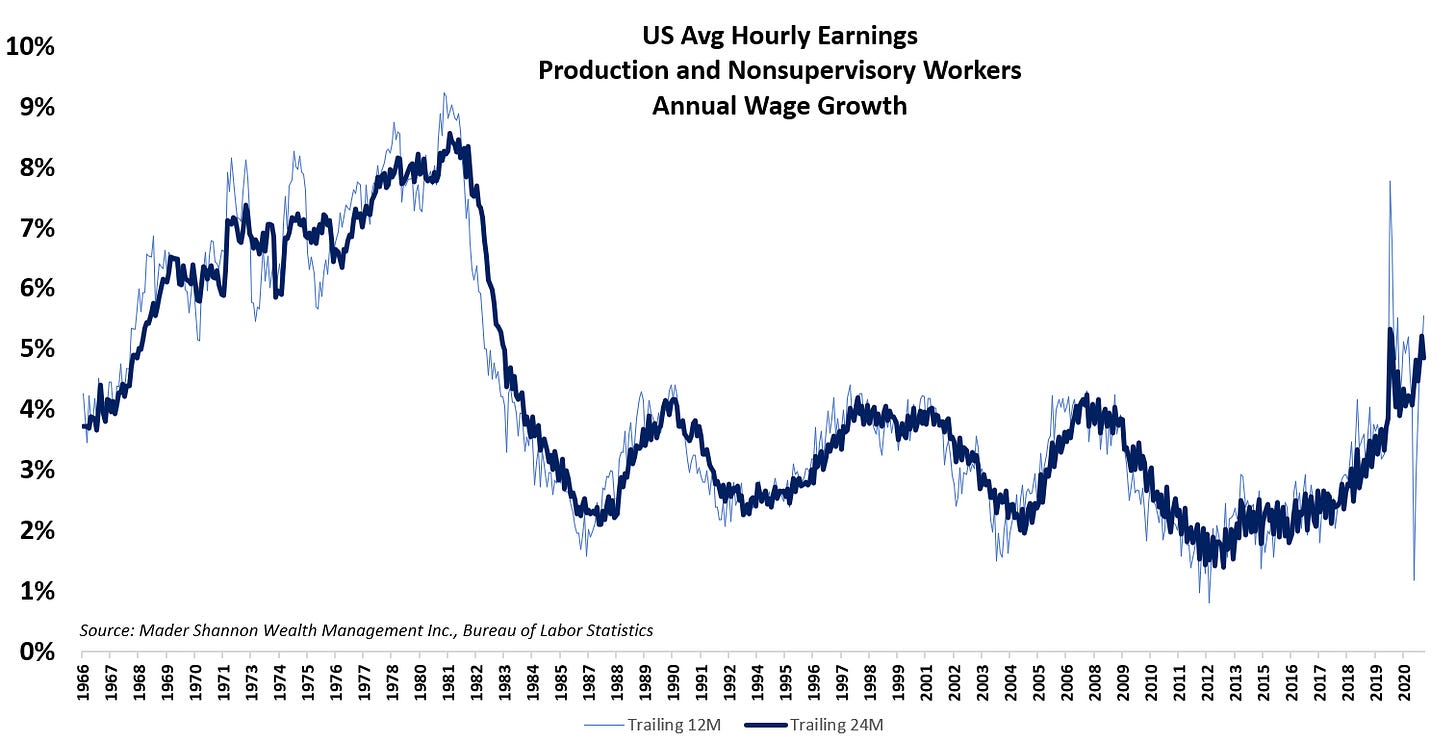

One solution, of course, is to raise wages in order to attract workers. And, again pulling from recent experience, businesses are doing so. I made more stops at fast food restaurants on my 12-hour road trip than I’d care to admit, and drive thru windows were consistently offering $14/hour or more for starting employees in the Midwest. It wasn’t so long ago (or maybe it was) that I was teenager making a healthy $7.25/hour raking gravel and pushing concrete in the hot sun. In any case, compensation is certainly on the rise – and not just along my drive through Missouri and Tennessee. Wages nationwide are up 4.6% over the last year, and rising even faster for production and non-supervisory workers. For that segment, which makes up about 80% of all U.S. workers, the rate of pay increases over the past 24M is better than at any time in the past 35 years.

So to recap, the unemployment rate is below average, wages are rising, and inflation, as has been covered by every media outlet this year, is the highest it’s been in over a decade. Why is it, then, that the Federal Reserve has yet to slow its latest round of quantitative easing and has indicated interest rates will remain at 0% for at least the next year? After all, their so-called dual mandate is to maintain full employment and price stability, which, by these measures, is well on track. Do we really still need such extreme levels of monetary stimulus?

The most obvious (and least cynical) explanation of the Fed’s inaction lies in the size of the labor force. The U-3 unemployment rate provides useful information about the state of the jobs market, but it’s not a perfect tool. The measure excludes from its calculation those who are no longer searching for jobs, like retirees and discouraged employment seekers – groups still feeling the lingering effects of COVID.

When lockdowns were underway and economic activity dried up, countless aging workers were coaxed (coerced?) into early retirement by way of attractive severance packages or layoffs. Higher wages today could entice them to re-enter the labor market, but it’s hard to predict how many of those who’ve tasted the sweet nectar of retired life are willing to return to the grind of a 9 to 5 – no matter the financial incentive. As for discouraged workers, the pandemic changed the way the world operates. Though millions of jobs are available, the skills needed to perform those jobs may not match the skills of those who’ve given up searching. There are also those actively prevented by COVID from returning to work, whether because loved ones need care, or because fear of contagion keeps them at home. These factors have resulted in a labor force that’s still 4.5 million persons smaller than it was in 2019, and when (or if) it will recover is anyone’s guess.

For its part, the Fed has been vocal about taking a broader approach to full employment than in the past, so they clearly believe a number of those who’ve left the labor will return, justifying a continuation of accommodative monetary policy. For the sake of employers nationwide, let’s hope they’re right.

Until then, enjoy some snapshots of my awesome week on the road.

Nothing in this post or on this site is intended as a recommendation or an offer to buy or sell securities. Posts on Means to a Trend are meant for informational and entertainment purposes only. I or my affiliates may hold positions in securities mentioned in posts. Please see my Disclosure page for more information.

The post Help Wanted: The U.S. Labor Market Continues to Tighten first appeared on Grindstone Intelligence.