How to Catch a Falling Knife: The Risks and Rewards of Buying the Dip

Stocks have declined in dramatic fashion over the last two weeks. With the S&P 500 index down 12% from its February 19th peak, some stocks are more than 50% off their year-to-date highs. At the risk of being redundant, I’ll phrase it another way. Several multi-billion dollar companies can be bought at half the price of what they were worth a month ago. If you’re an investor with cash on the sidelines, you’ve probably had the thought already: “Should I buy the dip?”

The answer is one you’ll have to choose for yourself, but here are a few things to consider before you pull the trigger.

The stocks that fall the most tend to bounce the most.

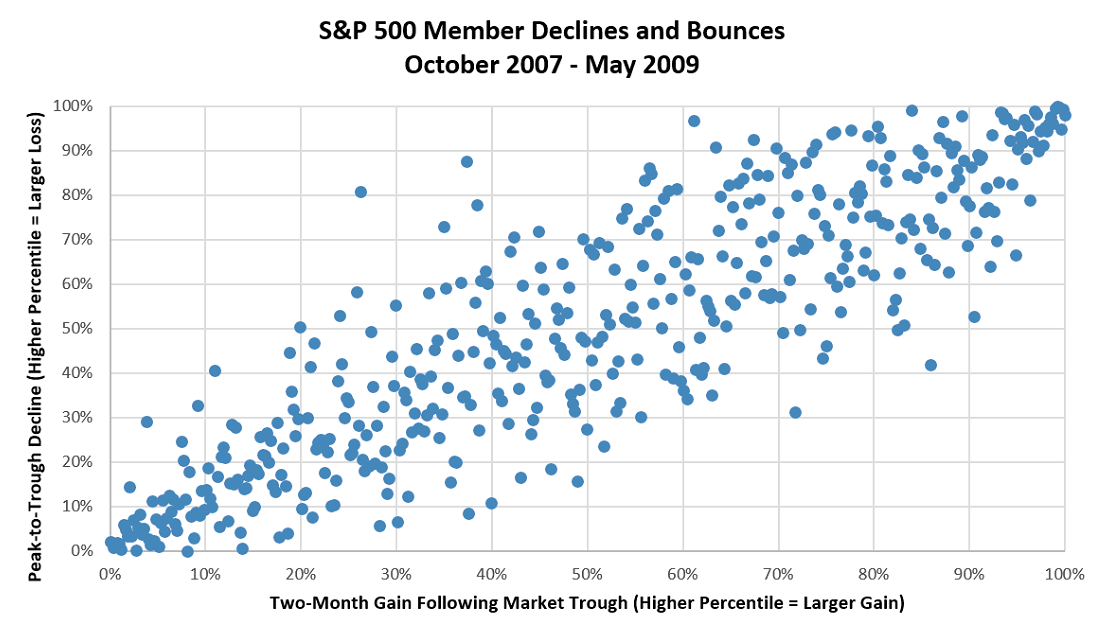

The idea that bigger declines are followed by bigger gains runs counter to the concept of momentum, but it’s held true in major declines over the past 20 years. The 2007-2009 was the most extreme example. When peak-to-trough declines and their ensuing bounces were ranked by percentile, there was a correlation of 0.88 between the two – the largest declines tended to result in the largest gains:

By comparison, the correlation in 2015 was the weakest of those I observed over the last 20 years, but still well into positive territory at 0.48. In this scenario though, the relationship was most clear when viewed in a slightly different light: the stocks that declined the least, bounced the least.

However, in each of the periods I studied, it was of utmost importance to catch the bounce in its early stages. Performance for the 60 days starting 2 months after the trough bore no relationship to the magnitude of decline. Here’s how things looked following the initial recovery in 2019:

Unfortunately, it’s not as easy as just going out and buying the biggest losers early. First, timing is everything. Just as it was impossible to know that March 24, 2000 would mark the peak of the Dotcom era, it’s impossible to know exactly which day prices will bottom. And when volatility becomes extreme, missing the entry by even one day has a material impact on returns.

We also need to acknowledge the presence of survivorship bias. In each date range, I excluded any company that was acquired or delisted during the period. (For example, rather than look in detail at each of the 22 instances in 2015 where price data for a stock ended, I chose to remove them all from the dataset.) This potentially skewed the data, but I don’t know by how much or in which direction. Removing a bankrupt stock obviously skews the result toward a positive correlation, but mergers are less clear: not all acquisitions during a decline are made at fire sale prices, and the delay between when a deal price is announced and the date the deal closes causes even more problems.

But just because I omitted those stocks from the chart doesn’t mean they should be ignored. We need to remember that sometimes, the worst stocks don’t recover at all. Sometimes they go to zero.

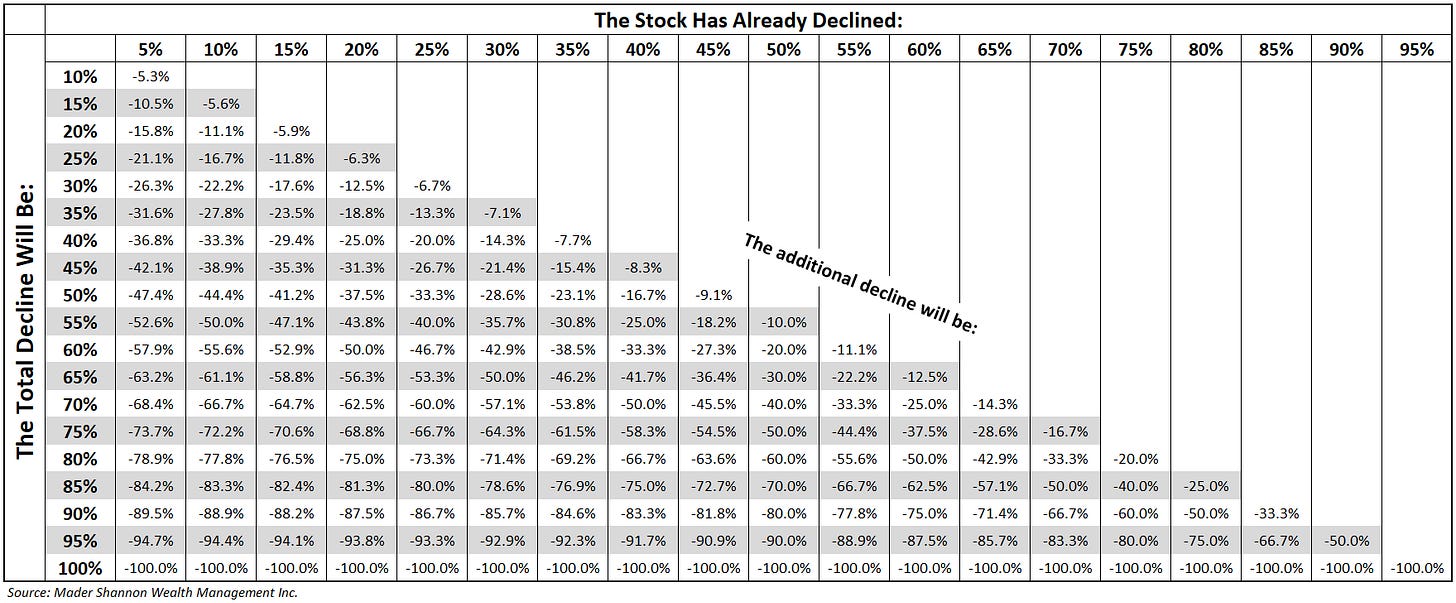

I’ve kept a table at my workspace for a few years now. It’s named ‘The Math of Market Declines’. When a stock (or the index) has crashed from its high, it’s easy to think the bottom must be near. Perhaps it is. But this table reminds me that being near the bottom isn’t always what it seems.

(Click table to see a larger version)

We don’t know in advance what the total decline on any selloff will be. But with 100 years of price data in the rearview mirror, we know that periodic declines in stock prices are less the exception than the rule. If you think the bottom right corner of this table seems extreme, you’re right. But the entire Dow Jones Industrial Average declined 89% from 1929 to 1932. It’s one thing to believe it won’t happen again (I sure hope it doesn’t). It’s another to pretend that it can’t.

Buying the dip offers plenty of reward, but don’t ignore the risks.

There’s an old saying that advises market participants not to try catching a falling knife. Rather, be patient, let it fall, and then safely pick it up off the floor. The saying isn’t that you can’t catch a falling knife – with some coordination, timing, and luck, you can certainly snag the spinning cutlery before it buries itself in that kitchen hardwood you overpaid for. Perhaps if you’ve practiced and prepared for the act, you might even be pretty good at it. It’s a trick guaranteed to impress your friends. But skilled or not, we’re all faced with the same question before we reach: can you bear the consequence of risking your hand to save the floor?

The post How to Catch a Falling Knife: The Risks and Rewards of Buying the Dip first appeared on Grindstone Intelligence.