Mid-Month Macro Musings - 1/17/2024

Pivot points and margin madness

Pivot Points

One of the most important inputs to the macroeconomic framework is central bank policy. Our lives as analysts would probably be a lot more enjoyable if we didn’t have to check the calendar for FedSpeak every morning, but that’s not the world we live in. As Marty Zweig said so many years ago, don’t fight the Fed.

Some folks out there will point in triumph to last year’s 20% stock market rise while the Federal Reserve continued to hike interest rates and claim that policy doesn’t matter. But that claim is rooted in a misunderstanding of how Fed policies are implemented these days. It’s what the Fed says that matters, not what they do.

And if you look at what Fed officials were saying, policy actions began to pivot in September and October of 2022 - exactly when the stock market put in its bear market lows.

It wasn’t always like this. Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan had a reputation for speaking while saying nothing at all. But his successor Ben Bernanke took a different approach. He believed that ‘forward-guidance’ could play an important role in helping to guide market expectations and transmit policy, so his Fed began to give more frequent updates and began publishing the quarterly Summary of Economic Projections, which details Fed officials’ outlooks for the economy.

Today, there are press conferences after every FOMC decision, and it seems there’s a never-ending flow of headlines from FOMC members voicing their opinions. In short, the primary tool of policymakers today is their words.

We wondered whether the frequency of FedSpeak could be used to identify policy pivots, and we weren’t disappointed with our findings. Check out the weekly speaking engagements for officials over the last few years. The spikes are noteworthy.

In the fall of 2020, the Fed had just unveiled their new framework for monetary policy, following several years of review. The new framework detailed an approach called Flexible Average Inflation Targeting (FAIT) which meant that if inflation ran below the Fed’s 2% target for some time, they’d be willing to let inflation run above 2% for some time after that in order to average 2% over the period. Ostensibly, that would allow the Fed to let the labor market run hotter for longer in order to achieve a broad and inclusive definition of full employment. Unsurprisingly, dovish changes in the September 2020 FOMC statement to reflect the new framework for policy required significant clarification and messaging from Fed officials.

The next major spike in FedSpeak was in March and April of 2022, when rate hikes began and the Fed was detailing plans for balance sheet reduction. But a bigger spike in speaking engagements came later that fall with the first Fed pivot: policy tightening stopped ramping in October 2022.

Yes, rate hikes would continue for nearly another year after that point. But those additional hikes were largely just fulfilling the forward guidance the Fed had already given. Language around that time stopped focusing about the ‘speed’ of rate hikes and instead began focusing on the end ‘level’ of rates. The very next Summary of Economic Projections after that policy pivot showed a peak policy rate of 5.1% - just 0.25% from where rates ended up.

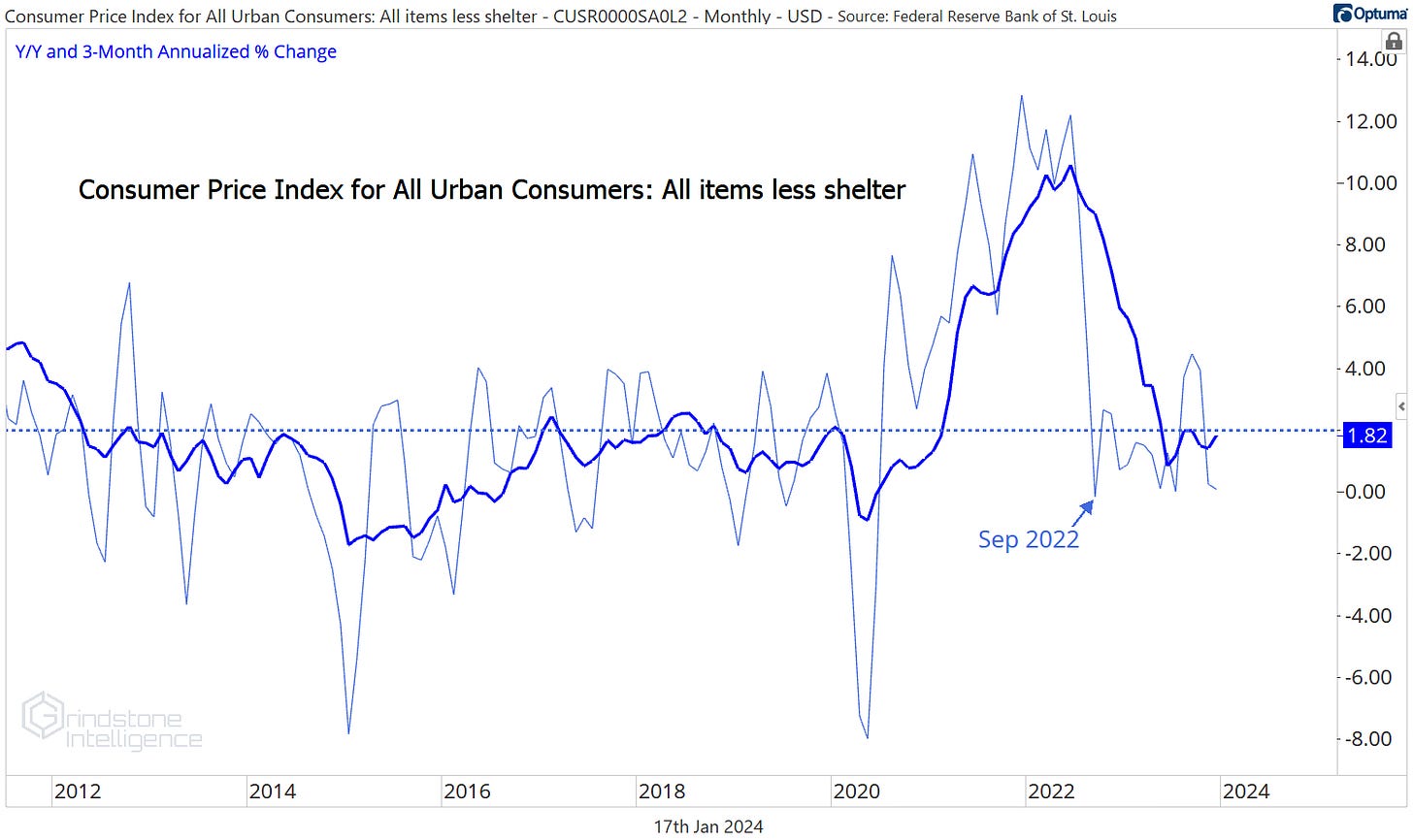

Supporting that leveling-off in policy was rapid disinflation. Year-over-year measures of price inflation were still near their peaks, but shorter-term measures were falling rapidly. By September 2022, 3-month annualized CPI ex-shelter had already dropped below the Fed’s 2% target. It’s stayed near that level ever since.

The latest pivot occurred last fall, when the Fed began shifting away from stable policy in favor of interest rate cuts. The 2-year Treasury yield tends to be a reliable reflection of where Fed policy is headed, and the reversal is pretty clear. To be clear, Fed officials didn’t actually do anything last fall to spark the downturn in rates. They just started talking about doing it.

And they gave those words more weight with the release of the December 2023 Summary of Economic Projections, which showed nearly 100 basis points of interest rate cuts for the current year.

Why is the Fed be talking about interest rate cuts when inflation is still running north of their 2% annual target? Because real interest rates are spiking. Last June, Fed Chair Jerome Powell said he would be targeting a level of real interest rates once policy reached a sufficiently restrictive level, and that meant rates would need to fall along with inflation in order to keep policy from getting progressively restrictive.

Here’s the current federal funds rate compared to CPI inflation. Real interest rates according to this measure are the highest they’ve been in 15 years.

And with inflation already moving towards target, the last thing Jerome Powell & Co. want to do is push the economy into a recession. They’ve been able to thread the needle so far, thanks to a remarkably resilient consumer that’s kept the economy churning at a healthy pace. But high rates are still taking their toll. Yesterday, the New York Federal Reserve’s Empire State Manufacturing Survey showed that current business conditions are worse than they’ve been at any time since at least 2006, save COVID.

Since the US economy is largely service-driven, manufacturing downturns don’t always result in economy-wide recessions. But the longer the goods economy struggles, the more like the contagion spreads. The Fed will seek to cut rates before that happens.

Margin Madness

We’re in the midst of the Q4 2023 reporting season, but everyoen is already looking ahead to where earnings will end up in Q4 2024. After a year in which earnings growth was largely flat - and may even end up in negative territory - S&P 500 profits are expected to grow 12% in 2024.

Major rebounds for earnings in Information Technology, Health Care, and Communication Services are driving the above-average growth estimate.

Growth in 2025 is expected to be nearly as strong. If bottom-up consensus estimates are to be believed, earnings for the S&P 500 will rebound at an annualized rate of 11.7% over the next 24 months. We’re led by some familiar names: 19.5% growth per year from the Tech sector, 14.6% growth from Health Care, and 13.9% from Communication Services.

The only trouble is, revenues are expected to grow at less than half the rate of earnings. That means the other half of earnings growth must come from margin expansion, and margins are already at high levels.

It’s not that the projected growth in margins is unprecedented. But in the past decade, it’s taken significant changes like tax reform (2018) or a recession rebound (including the unwind of loan loss provisions by the banks in 2021) to see the type of improvement analysts are expecting as a matter of course over the next 24 months.

Earnings and revenue estimates imply that profit margins will hit new highs in 5 of the 11 sectors - 6 if you exclude the aforementioned 2021 outlier for the Financials. All but the Health Care sector are expected to turn in margins that are better than the 10 year average.

We won’t go so far as to say these margin projections can’t be achieved. But we’re a bit skeptical.

That’s all for today. Until next time.