Mid-Month Macro Musings - 12/19/2023

Rate cuts in 2024 and a reality check for future earnings growth

No more hikes

Once again, the Federal Reserve kept their target for overnight lending rates unchanged at last week’s FOMC meeting. It’s safe to say that the hiking phase of this policy cycle has come to an end.

Now the question becomes how long rates will stay at this elevated level.

If the Fed’s own projections are to be believed, cuts are set to begin sometime next year. The Summary of Economic Projections shows a median federal funds rate expectation of 4.6% 12 months from now and a drop to 3.6% by the end of 2025.

Market prices imply those cuts will start in March, just a few months away. Yet Fed officials in recent days have poured some cold water on hopes of such a quick reversal. Raphael Bostic, President of the Atlanta Fed and one who’s been on the leading edge of policy adjustments over the past two years, said on Friday that he’s expecting only two cuts next year, with the first occurring sometime in the third quarter. Economic thought leader John Williams, President of the New York Fed, was similarly dispositioned. He said in an interview that it’s premature to even be thinking about cuts right now, and the Fed must be ready to hike again if needed. Even the dovishly-inclined president of the Chicago Fed, Austan Goolsbee, said he doesn’t expect rates to be significantly lower a year from now - though he, at least, declined to rule out a March cut.

The consensus is clear: the Fed can afford to take a wait and see approach as inflation slowly trends towards policymakers’ 2% annual target.

That doesn’t mean the Fed has to wait until inflation comes all the way down to 2% before making an adjustment. Real interest rates rise as inflation falls, even if policy remains unchanged. That means the Fed will need to lower rates along with inflation to keep monetary policy from getting progressively more restrictive. Fed Chair Powell began detailing that concept all the way back in June, so it would be surprising if he abandoned it now. And if the Fed truly wants to achieve a soft landing, they’ll have to be careful not to let policy get too tight.

For now, they’re successfully threading that needle. Despite the fastest hiking cycle in deacdes, economic activity continues to be healthy. After a blowout GDP print of 5.2% in the third quarter - which almost everyone agreed was an aberration - growth in the fourth quarter is tracking at a respectable 2.6% rate according to the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow estimate. The consensus expectation on Wall Street is just 1%.

Strong jobs and consumer spending are responsible for the most recent upward adjustments to the GDPNow number.

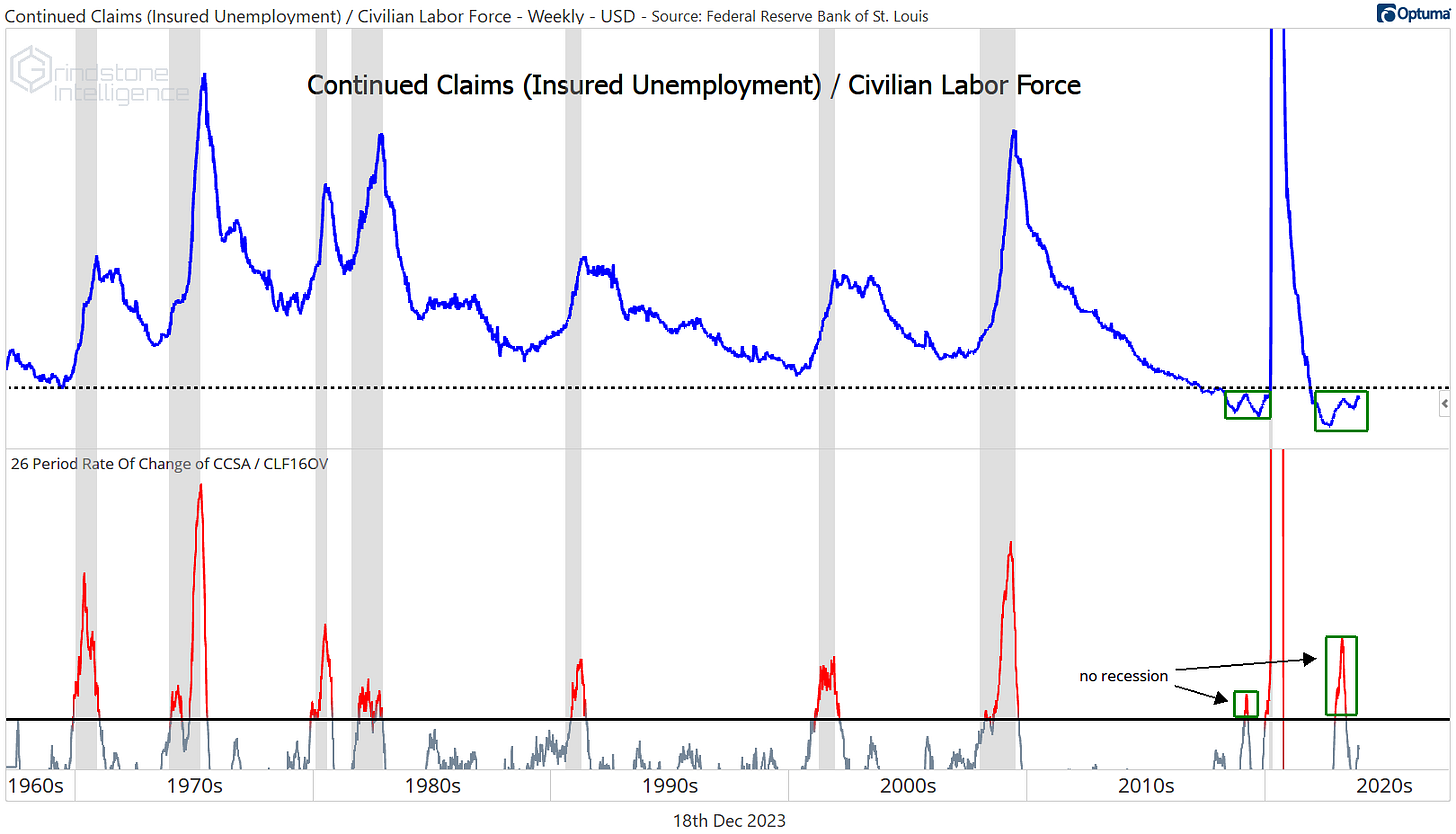

The unemployment rate fell back to 3.7% in November, down from October’s peak rate of 3.9%. That contrasts with continuing jobless claims, which are near their highest level in almost two years. Claims have historically been a pretty solid leading indicator - they rise in advance of recessions - and recessions have almost always ensued when claims rise as much as they have over the past 6 months.

However, if you compare the level of continuing claims - rather than the trend - to the size of the labor force, we're coming out of what's clearly the tightest labor market on record.

Does it matter where we’re coming from? Every time claims rose at this pace from the 1960s to 2018, a recession occurred. The level of claims didn’t matter – only their trend.

But in 2019 we were dealing with the tightest labor market on record.

When claims rose from that level and triggered a recession warning, no recession followed (at least not until the pandemic shutdowns caused one.) We don’t know what’s in store for the economy this time around, but the labor market is still in a good place overall. And with retail sales re-accelerating in November, it’s pretty clear we’re not in a recession right now.

If it’s not recession, what else could spoil the Fed’s well-laid plans? Perhaps a resurgence in inflation?

The last time inflation ran rampant in the United States, an Arthur Burns-led Federal Reserve backed away from their fight too early, cutting rates in response to economic weakness and allowing price pressures to reignite. The blame shouldn’t be entirely laid at Burns’ feet, though. A series of oil price shocks also had a hand, and those were completely out of his control.

So are the global disruptions plaguing the world today. Oil is still the world’s single-most important commodity, and wars between Russia and Ukraine and the turmoil in the Middle East following the deadly terrorist attack in Israel have the potential to disrupt energy activity in several of the largest oil-producing countries.

It’s disruptions in global shipping that have caught our eye in recent weeks, though.

About 6% of global trade flows through the Panama Canal, a 50-mile waterway between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Drought conditions have severely restricted the canal’s capacity this fall, resulting in longer wait times and higher costs. A recent Bloomberg article detailed the severity of the issue and the desperation of shippers. Whenever a ship with a reservation cancels, their slot is auctioned off by the Panama Canal Authority. A year ago, those slots went for an average of $173,000 (in addition to the usual transit fee, which can be as much as $1,000,000). Auctioned slots this year have gone for as much as $4,000,0000.

Desperate shippers are left with the option of waiting in line at Panama, heading around the Cape of Good Hope, or trying their luck at the Suez Canal.

Unfortunately, the Suez Canal has issues of its own. Some 15% of global trade flows through the Red Sea, And now many of the world’s largest shippers - including Maersk, MSC, and BP - are refusing to utilize the route.

The move comes after Iran-aligned Houthi militants increased their attacks on ships passing through the Sea, which they say is a response to Israel’s incursion into Gaza.

That means more ships around the Cape of Good Hope, longer lead times, and more fuel costs. We’ll leave it to the economists as to whether these disruptions are enough to materially alter the course of inflation here in the US. But it’s certainly something we’ll be watching.

Optimistic earnings outlook… Perhaps too optimistic

S&P 500 earnings growth is expected to end the year in negative territory, despite the 23% year-to-date rally in stock prices. The 3.4% index-level EPS decline is being led by significant drops in the Real Estate, Energy, Materials, and Health Care sectors.

Growth over the next two years, though, is expected to rebound sharply. If bottom-up consensus estimates are to be believed, earnings for the S&P 500 will rebound at an annualized rate of 11.5% over the next 24 months, led by 19% growth per year from the Tech sector, 15% growth from Health Care, and 14% from Communication Services.

The only trouble is, revenues are expected to grow at just half the rate of earnings. That means half of earnings growth must come from margin expansion, and margins are already at high levels. The most extreme offender is Information Technology, where estimates imply a record profit margin of 27.3% in 2025, up from 2023’s 23.3%.

Record high margins are also expected for Consumer Discretionary, Communication Services, and Industrials. All told, it would mean 150 basis points of expansion for the S&P 500 over the next two years.

It’s not that the projected growth in margins is unprecedented. But in the past decade, it’s taken significant changes like tax reform (2018) or a recession rebound (including the unwind of loan loss provisions by the banks in 2021) to see the type of improvement analysts are expecting as a matter of course over the next 24 months.

We won’t go so far as to say it can’t happen. But we’re a bit skeptical.

That’s all for today. Until next time.