Mid-Month Macro Musings

Loosening Labor Market

Tomorrow, the Federal Reserve will wrap up its 2-day monetary policy meeting. No one expects them to take any action on interest rates this time around, especially given higher than expected inflation readings to start the year. Rather than what the Fed is doing, we’re interested in what they’re saying. An update to the Fed’s quarterly Summary of Economic Projections should give us insight into how Fed officials are viewing the disappointing price data and how many rate cuts are still on the horizon for 2024. Just as important will be Chair Jerome Powell’s post-meeting press conference.

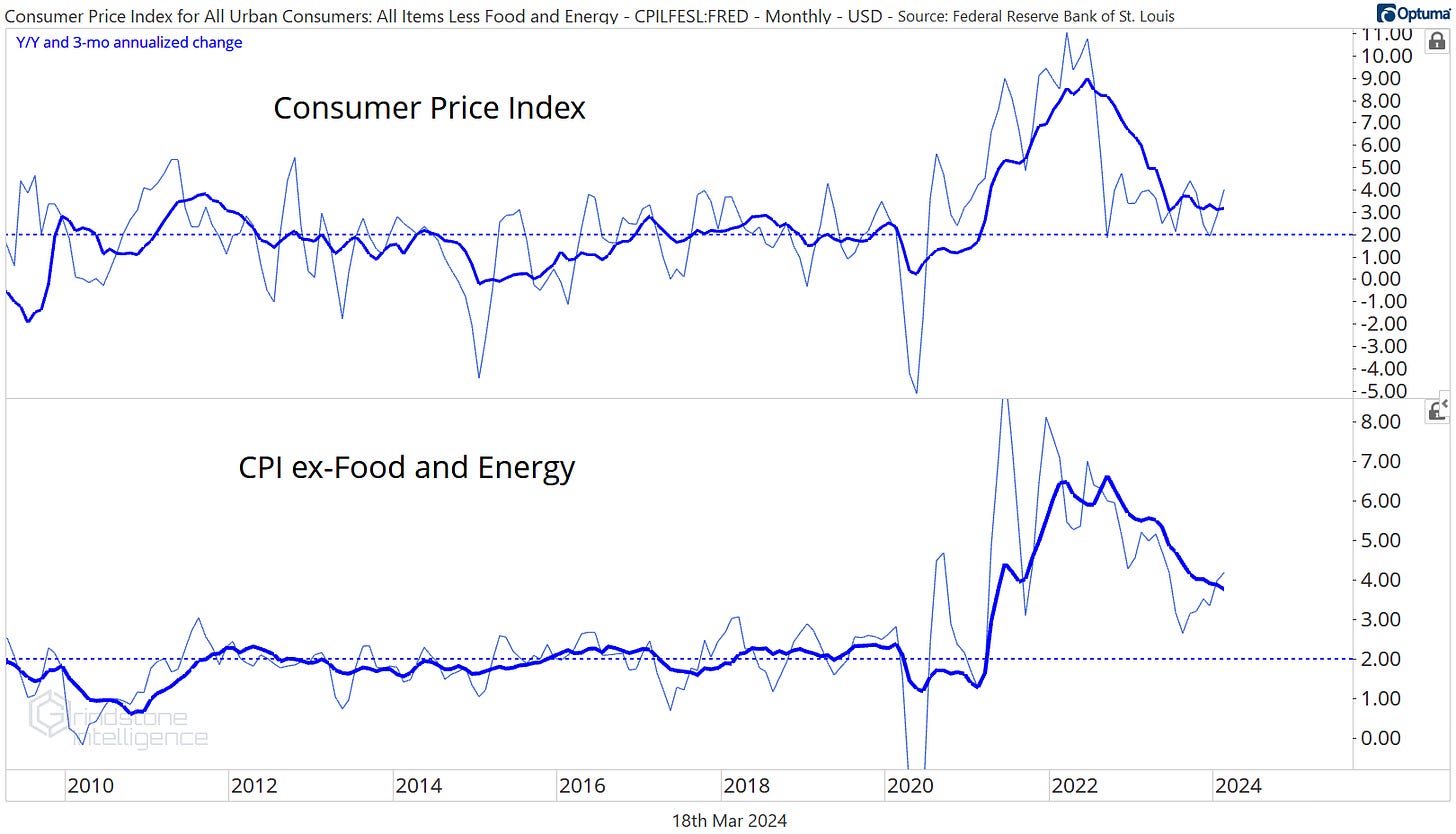

Here’s what Powell and his colleagues are seeing. The Consumer Price Index surprised to the upside last Tuesday. Inflation rose to a 3.2% annual rate, up from the prior month’s reading of 3.1%. Core prices rose 3.8% year-over-year.

The short-term readings are even worse. On a 3-month annualized basis, headline CPI rose 4% and has remained stubbornly above the Fed’s 2% for the last 18 months. 3-month annualized core CPI climbed to its highest level since last May.

And with commodity prices moving higher to start the year, rising input costs should be top of mind for the price-focused setters of monetary policy. The Fed absolutely can’t afford to let prices reaccelerate - not with how adamant they’ve been about fulfilling that half of their dual mandate - and that forces them to keep a tight rein on economic activity through a policy of higher interest rates for longer.

We can see the impact higher inflation readings have had on the market. Back in mid-January, the market was pricing in as many as seven 0.25% interest rate cuts in 2024, based on implied interest rates for December. Today, we’re looking for just 3.

Fortunately for the Fed, they’ve got one thing working in their favor on the inflation front. CPI excluding shelter has been below the Fed’s 2% annual inflation target since June. On a 3-month annualized basis, this measure of prices has been subdued since October 2022.

If shelter inflation continues to normalize, following the path of home prices and rental rates, that should help offset the impact of energy prices.

Unfortunately, complete normalization of shelter costs - which comprise a third of the CPI - will take time. And the longer interest rates remain elevated, the higher the risk of tight policy tipping the economy into recession.

Consumption has slowed significantly to start the year. In January, retail sales dipped into negative territory compared to the prior year. Over the last 20 years, that’s something we’ve only seen during recessions.

Poor January weather and a pull-forward of demand in December are being blamed for the weak reading, but better weather in February didn’t lead to much of a rebound. We’ll remind our readers that weather is like alcohol - it gets blamed for a lot of things it didn’t do.

Whether or not consumers can afford to ramp their level of spend back up will largely depend on 2 factors: the availability of credit and their incomes from employment.

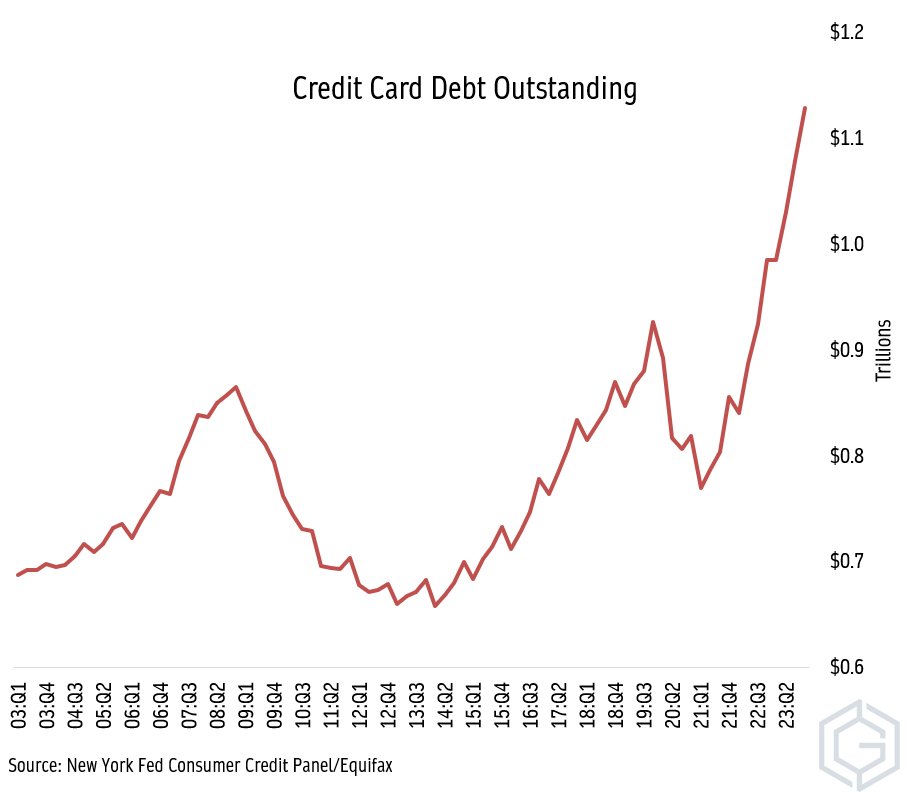

December’s surge in spending was fueled by borrowing. According to the New York Fed’s Household Debt and Credit report, credit card debt surged to more than $1.1 trillion dollars in Q4.

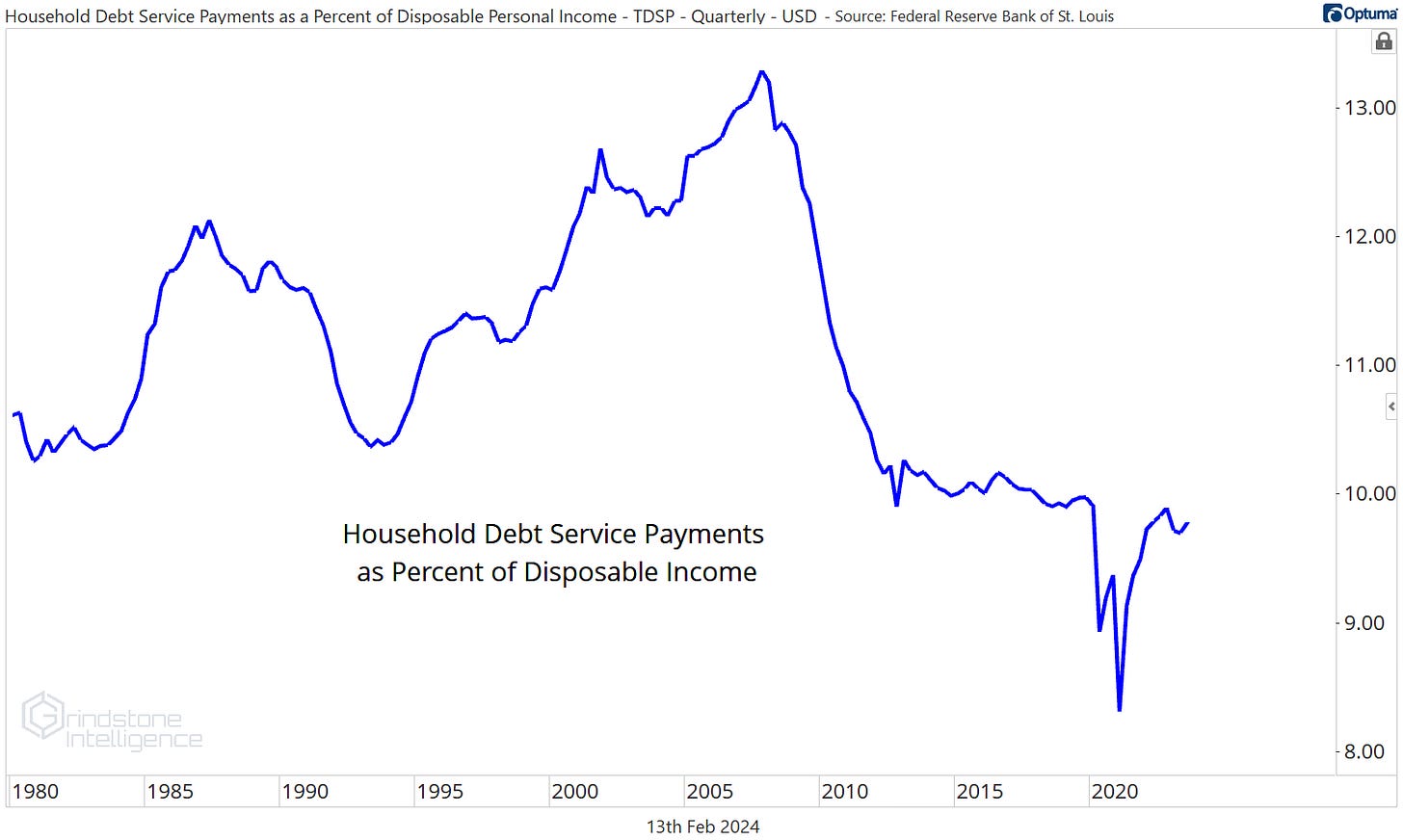

But debt levels only become a widespread problem when people can’t pay their bills. And thanks to rising incomes, debt is more manageable than it was in the 40 years prior to 2020. Household debt service payments as a percent of disposable income were still below 10% in the third quarter.

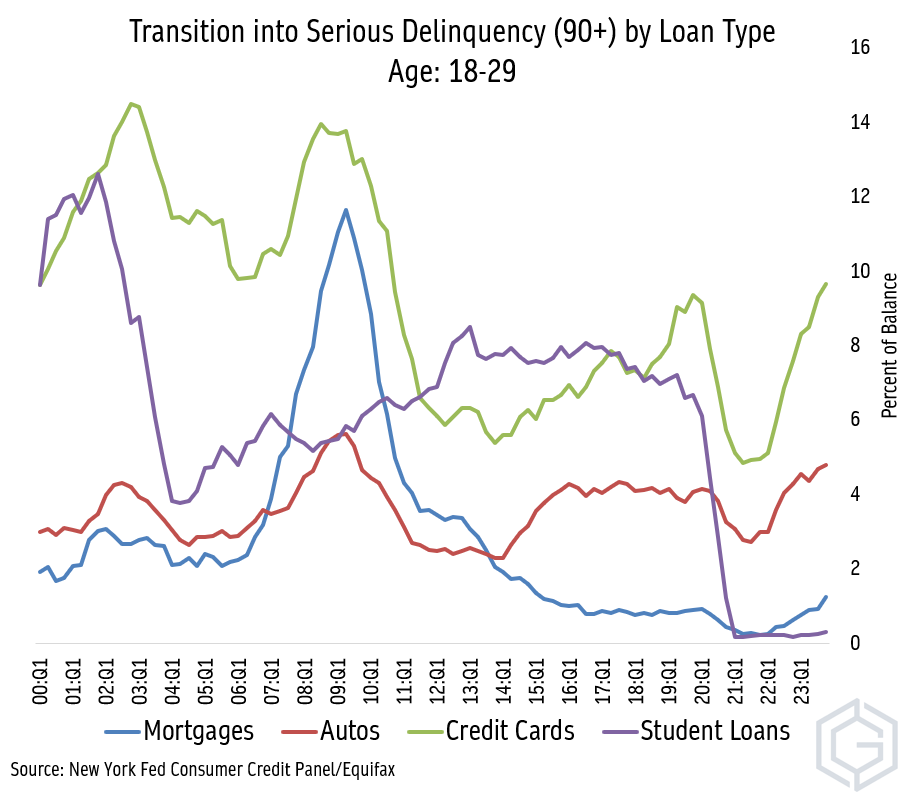

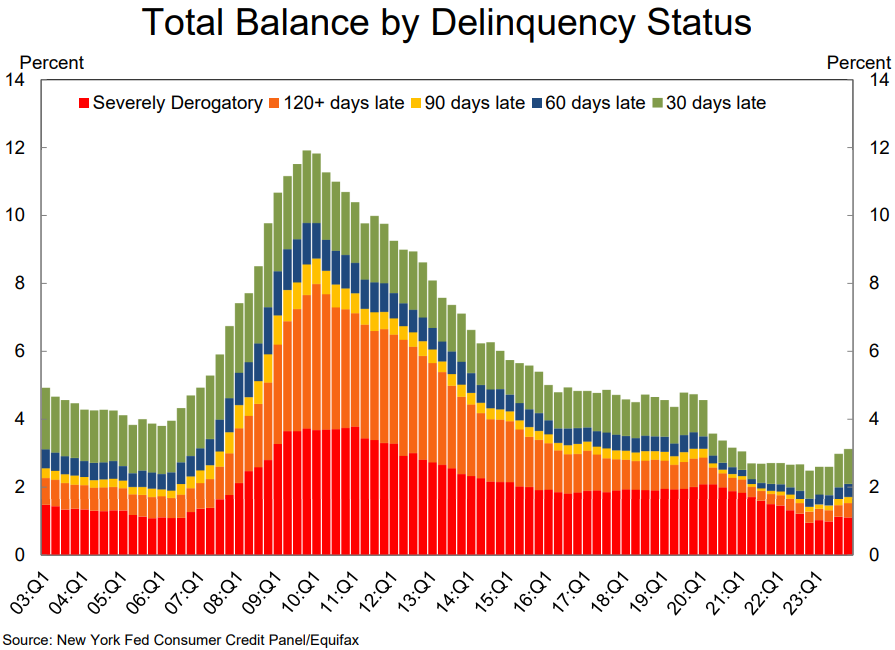

Unfortunately, younger consumers are feeling the adverse effects of higher debt levels the most. For 18-29 year-olds, delinquencies are setting new incremental highs for credit cards, auto loans, and mortgages. That’s before we’ve even felt the full weight of student loan payment resumptions.

The good news is, total delinquencies for all US households including borrowings on credit cards, auto loans, and mortgages is only about half of what it was pre-COVID. Though there are pockets of weakness that may spread, for now, household balance sheets are in good shape.

It’s not credit, but the loosening in the labor market that’s caught our eye in recent weeks. Let’s get one thing straight: The labor market is still tight.

The unemployment rate right now is as low as anything we saw from the 1970s to the late 2010s.

And while continuing jobless claims have risen from their lows, if we compare claims to the size of the labor force, the current labor market is still better than it was even in the late 1960s.

There are still plenty of job openings, too. Take a look at the number of job openings compared to the number of unemployed workers from the monthly BLS payrolls report. No, this isn’t spring 2022 when there were more than 2 jobs available for every applicant, but at 1.4x, this ratio is still better than anything we saw in the pre-COVID era.

It’s not the level of tightness in the labor market that’s the problem. It’s the trend. Things are clearly moving the wrong direction for workers. At 3.9%, the unemployment rate is the highest it’s been in 2 years. And if we look at survey data from the National Federation of Independent Business, employers are pulling back. The number of small businesses with job opening that are hard to fill has declined back to pre-COVID levels. The same is true for the index of compensation plans.

Even weaker are hiring plans, which have dropped to a level not seen since late 2016 (excluding COVID, of course). And if we look at the number of small businesses citing labor quality as their single most important problem (a reflection of employers hiring anyone they can find in a competitive market), we see the same thing.

Survey data has its flaws, sure (especially in surveys where respondents tend to respond differently based on who’s sitting in the oval office.) Still, these trends are a bad look for the labor market and something to keep an eye on in the coming months.

A loosening in the labor market was both a necessary and inevitable outcome of the Fed’s war against inflation. But with the much-heralded soft landing nearly within their grasp, you can bet the Fed is wary of letting it slip away. If the weakness in employment gets more pronounced, look for rate cut expectations to make a comeback.

Until next time.