Mid-Month Macro Update

King Consumer

Reports of the death of the US consumer have been greatly exaggerated.

This morning, the US Census Bureau released their advance estimate for September Retail Sales. The number blew past expectations, coming in 0.7% higher than sales in August, which were also revised higher. On a year-over-year basis, retail and food services sales accelerated to 3.8%.

Just a few short weeks ago, the consensus view on Wall Street was that the US consumer was set for a major slowdown. Layoff announcements had been on the rise since the beginning of the year, wage growth was slowing, and student loan payments were set to resume in October. On top of it all, everyone agreed that excess savings from the pandemic – when direct checks from the government caused personal incomes to spike at an unprecedented rate – were drying up. An August paper from the San Francisco Federal Reserve estimated that excess savings had been entirely spent.

About that…

At the end of September, the US Bureau of Economic Analysis published a major revision to their report on Personal Income and Outlays – the report that most economists were using as the basis of their excess savings estimate. Here’s a side-by-side comparison of the data before and after the BEA’s revisions.

The data was (laughably) revised all the way back to 1979, but the biggest adjustments can be seen in the decade leading up to the pandemic. Personal savings over that entire period were significantly less than previously thought. That lowers the baseline savings rate against which excess savings are calculated, mathematically raising the cumulative excess.

In short, everyone now seems to agree that consumers still have plenty to spend!

A recent Bloomberg article highlighted the changes. JPMorgan economists Michael Hanson and Murat Tasci increased their estimate of remaining excess savings to $1.2T from $400M. Economists at Citigroup and UBS raised their own estimates to more than $1T, too. And Mark Zandi from Moody’s Analytics is all the way up at $1.8T! Even more conservative estimates – like those using the same method as the San Francisco Fed – put remaining savings somewhere near half a trillion dollars.

Consumer still have money to spend.

They’re making more than ever, too, thanks to a labor market that remains tight. Last week, the Bureau of Labor Statistic reported another 336,000 jobs added in September – the best pace of hiring since a blowout report in January. Job openings have come off their highs, but there are still many more employers looking to hire than there are people looking for jobs.

The tightness has given workers the type of advantage that they haven’t had in decades.

The International Brotherhood of Teamsters reached an historic agreement with UPS over summer, which included significant wage and working condition concessions from the package delivery company. According to the Teamsters, wage increases for full-timers will keep UPS Teamsters the highest paid delivery drivers in the nation, improving their average top rate to $49 per hour. And in another big win, UPS will equip in-cab A/C in all larger delivery vehicles, sprinter vans, and package cars purchased after Jan. 1, 2024. The Teamsters estimate the incremental costs for UPS to be near $30 billion.

The United Auto Workers union is looking for a big win of its own. Contracts with the Big 3 US automakers expired last month, which gave new UAW President Shawn Fain a chance to set new industry standards. He opened negotiations with calls for a 40% pay increase, a 32-hour workweek, and improved retirement benefits, among other things. When auto industry executives failed to meet those demands, Fain announced targeted strikes at each of the Big 3 automakers. Strike activity has been ramping up over the past few weeks, and though auto workers surely won’t get everything they initially asked for, the contract will be a significant improvement from the prior agreement.

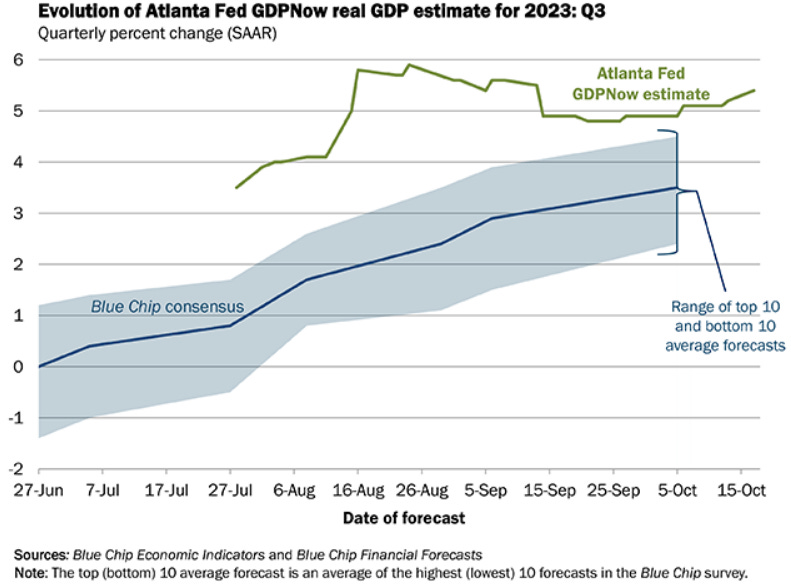

Of course, strikes can have negative economic repercussions, as can rapidly rising labor costs. We discussed those last month. Perhaps those ill effects will begin to affect the economy in the coming quarters. But they aren’t dragging the economy down yet. The Atlanta Fed just revised their third quarter GDP estimate to a 5.4% annualized rate. That would be the fastest rate of growth since the end of 2021, when we were still rebounding from the COVID shutdowns.

We’ll get the government’s estimate of Q3 GDP next week, but it looks like that ‘inevitable’ recession will have to be postponed a bit longer.

Mission Accomplished… Maybe

Slowly but surely, inflation is headed back towards the Fed’s 2% annual target. Last week, the US Census Bureau reported that the Consumer Price Index rose at a 3.7% annual rate, up from June’s recent low of 3.0%. Most of the recent acceleration, however, can be attributed to energy prices.

Inflation excluding food and energy – called core inflation – continues to trend lower, and that’s a good thing.

Economists regularly cite core inflation not because food and energy prices don’t matter, but because food and energy prices tend to be volatile and not indicative of broader price pressures in the economy. In short, core inflation has traditionally been a better predictor of future inflation.

However, sustained increases in energy prices – not just volatile swings – can lead to broader price pressures. That was a major theme during 2021 and 2022, and one that was initially (and incorrectly) discounted by policy makers. When fuel prices rise, so do production and transportation costs, and over time, those costs can spill over to consumers. That’s a trend worth keeping an eye on in the coming months.

Another common component of the CPI to exclude is the cost of housing. And at 1.98%, the CPI for all items less shelter couldn’t be any closer to the Fed’s target.

Again, the reason for excluding shelter isn’t because housing costs don’t matter. Housing is the biggest monthly outlay for most Americans. It’s incredibly important. Instead, shelter is often excluded because the government’s method for measuring housing inflation serially lags the real world experience.

Consider this. CPI for shelter currently stands at 7.1%. Meanwhile, the most recent Case/Shiller Home Price Index rose at just a 1% annual rate. And Zillow’s Observed Rent Index is all the way down at 3.2%.

Policymakers now have to ask themselves whether the recent uptick in energy prices, coupled with a resurgent US consumer, is enough to warrant additional rate hikes.

FOMC Members are split on the issue. Atlanta Fed President Rafael Bostic has been advocating a patient approach. He believes rates are now restrictive enough to bring inflation all the way down to 2%. Bostic’s dovish stance is important because he hasn’t always been a dove. In fact, he was the among the first and most vocal FOMC members to begin publicly advocating for interest rate hikes.

Meanwhile, Federal Reserve Board Governor Michelle Bowman and Minneapolis President Neel Kashkari have consistently voiced their opinion that an additional hike – or hikes – will be needed to successfully quell prices.

For Bostic’s part, he believes we need to assess the effects of already completed interest rate hikes on the economy. Those effects take place with long and variable lags, and with more than 5% of rate increases in the recent rearview mirror, Bostic believes the economy won’t fully feel the weight of the Fed’s past adjustments until sometime next year.

Another recent theme from policymakers has been the rise in long-term interest rates. Since April, the 10-year Treasury yield has risen 140 basis points, and now stands at the highest level since 2007.

Some FOMC members believe that higher long-term rates have reduced the need for additional hikes on the short end of the curve. Others aren’t so sure. The split opinion shouldn’t surprise anyone who read the most recent SEP.

The Summary of Economic Projections is where Fed officials detail their estimates for future economic data and policy actions. Check out the range of estimates for the federal funds rate at year-end 2025: the most hawkish FOMC member sees rates above 5.5% by then, while the most dovish sees them down near 2.5%. Even in a committee often derided for groupthink, there’s nothing that remotely resembles a consensus about what the future will look like.

If there is agreement, it’s that rates in the future will be lower than they are now. Barring a significant inflationary surprise, the worst of the monetary policy tightening cycle is a thing of the past.

It’s not just a US phenomenon, either. Central banks around the world are starting to change course. We’re coming off one of the broadest monetary policy tightening cycles ever, where 95% of the central banks tracked by the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) were in a hawkish regime. That number dipped to 86% at the end of September.

And that reversal is set to continue. Bloomberg data tracking current and futures-implied policy rates for more than 30 central banks shows that 80% of those banks will have cut rates by this time next year.

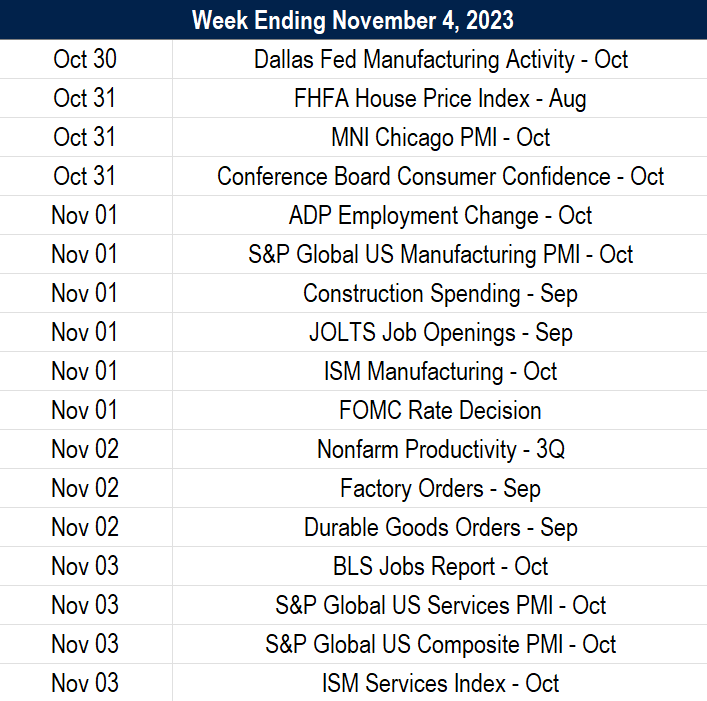

A Look at What’s Ahead

The post Mid-Month Macro Update first appeared on Grindstone Intelligence.