Mid-Month Macro Update

The Fed’s Fight Against Inflation is Coming to a Close

After the most aggressive interest rate hiking cycle in 40 years, the Federal Reserve is close to achieving its goal.

Yes, annual measures of inflation are still above the Fed’s 2% target, and the FOMC will most likely raise rates again at next week’s policy meeting. We usually refrain from making economic forecasts, but we believe next week’s hike will likely be the final interest rate move of 2023. Consider the following:

Inflation is moderating faster than even the optimistic forecasters had anticipated. During June, CPI slowed to a 2.969% annual rate, less than half of the rate at year-end, and just one-third the rate from a year ago, when prices pressures were at their peak. That decline bodes well for next week’s report on the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, the PCE Deflator.

Headline PCE has declined steadily over the past year, supported by falling energy prices. However, the Core measure, which excludes energy, has remained stubbornly elevated. So how can we be so optimistic about the outlook for prices when the biggest drag on inflation has been energy, and energy costs are unlikely to continue falling at such a rapid pace? For one, those falling energy prices will transmit to the rest of the economy via lower input and transportation costs. Additionally, the largest contributor to higher prices is becoming less and less of a problem.

Shelter inflation (which accounts for roughly one-third of the CPI) peaked in March. That measure tends to follow home prices (albeit with a considerable lag), which right now are negative 1.5% from one year ago. In other words, we expect shelter inflation to normalize rather quickly over the coming months.

And CPI ex-shelter has been running at the Fed’s target since last September.

Last week’s most surprising news item further solidified our view that the Fed’s final hike is coming next week. We’re talking, of course, about the resignation of St. Louis Federal Reserve President James Bullard, who will become a dean at Purdue’s School of Business. Bullard was the Fed’s most prominent hawk, and his exit creates a leadership vacuum in the camp for further rate hikes. Longtime hawk Esther George stepped down earlier this year after reaching the mandatory retirement age earlier this year, and Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester will have to do the same in early 2024. That leaves relative newcomers like Governor Chris Waller and Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari to carry the mantle. We’re not sure their opinions alone can sway the Committee.

In the meantime, central banks in Europe and the United Kingdom are still in the middle of their own rate hike cycles, with no end in sight. And it’s rumored that the Bank of Japan could take a tiny step back from yield curve control at its upcoming meeting. The potential for tighter monetary policy in the rest of the developed world – at the same time the Fed nears peak rates – has pushed the US Dollar Index to new 52-week lows.

A weaker Dollar is a welcome sight for stock market investors here in the US. The Dollar’s rise in 2022 was a major headwind to equity returns – it’s reversal has had the opposite effect.

The weakness should benefit corporate earnings, too, since about 40% of S&P 500 revenues come from overseas. The benefit is partially just an accounting trick: overseas earnings must be translated into US Dollars each earnings period, so a weaker Dollar results in positive exchange rate impacts to a company’s bottom line. But there are tangible positive impacts, too. US products become more attractive as the value of the Dollar falls, driving increased export activity.

Unfortunately, the positive impacts won’t be enough to result in earnings growth for the second quarter. The Q2 2023 reporting season is just getting underway, and consensus expectations are for S&P 500 earnings to decline 7.0%. It would be the third consecutive quarterly earnings decline for the index, this one driven by a 50% drop in earnings for the Energy sector.

Margin weakness is to blame. The majority of sectors are facing margin declines, both in Q2 and for the year. Profit margins for the index are set to contract to 12.4% in 2023, down from a peak of 13.7% in Q1 2022. Analysts are hoping they’ll rebound to 12.9% next year, though, driving a 10% boost to S&P 500 earnings.

That bullish outcome will depend on whether or not the Federal Reserve has already gone too far. The nation’s monetary authority has a long and storied history of tipping the economy into recession. Perhaps they’ve done it again?

Over the last year, recession doomsdayers have time and again been forced to push back their expectations of an economic downturn. This year, with the stock market rallying, many economists and strategists have pulled a recession out of their forecasts entirely, betting instead on a ‘soft-landing’ scenario.

What’s been driving the resilient US economy? The resilient US consumer. They have jobs, they have excess savings from the pandemic, and debt service costs are low. As long as all three tailwinds remain in place, people will keep on spending money.

Jobs

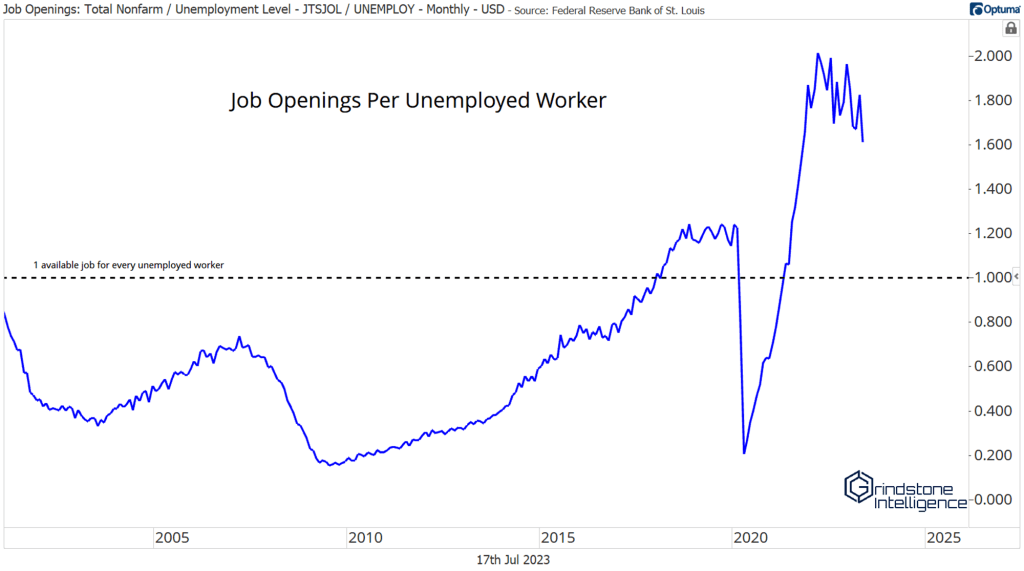

The labor market remains tight, despite some recent signs of softening. There are 1.6 jobs available for every unemployed person – less than where we were this time last year, but still at a level that would be inconceivable 5 or 10 years ago.

And the tight market is having an impressive effect on the labor force. The prime age participation rate is at its highest point in 20 years!

Savings

Excess savings are drying up. Here’s an insightful chart from the economics team at Bloomberg. The bottom 40% of households now have lower real cash balances than they did prior to COVID.

Despite that, estimates of cumulative excess savings range are as high $1T – that could fuel quite a bit more spending from the more affluent households that hold it.

Moreover, while revolving credit balances are rising, they remain below pre-pandemic levels – at least according to JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon on last week’s earnings call. Rebuilding credit balances could allow spending to continue even after excess savings have disappeared.

Debt

Debt service costs for consumers have been in recent years low thanks to the low interest rates that came in the wake of pandemic era stimulus, the pay down of revolving credit balances, and the deferment of student loan payments. Now, mortgage rates are at their highest levels in 15 years, use of revolving credit is on the rise, and the moratorium on student loan payments is about to expire.

Will the return of student loans force consumers to pull back on discretionary spending? Almost certainly. And the impact could be large enough to bring retail activity to a grinding halt. What actually happens is anyone’s guess. Recall that roughly 12% of student loans were delinquent prior to the pandemic. And now half of Washington is telling borrowers that avoiding payments could pay off big with loan forgiveness.

Politics aside, the reality is that many people have no intention of restarting their payments later this year, especially if it would mean changing spending habits.

A Look at What’s Ahead

The post Mid-Month Macro Update first appeared on Grindstone Intelligence.