Oil’s Supply Problem

During the last two years, rising costs have permeated our lives. It started, of course, with a pandemic. While factories and production facilities were locked down to stem the spread of infection, governments and monetary authorities across the globe were responding to COVID with unprecedented stimulus and fueling a surge in demand for goods. The supply/demand mismatch resulted in backlogged ports and input shortages and has pushed domestic inflation to the highest level in 40 years.

But just when it looked like the worst of the pandemic-era disruptions might finally be in the rearview mirror, recent geopolitical events in Europe spurred renewed price pressures. Ukraine and Russia together account for nearly a quarter of global grain trade – with the two engaged in military conflict, agriculture prices have surged. Wheat has skyrocketed to all-time highs.

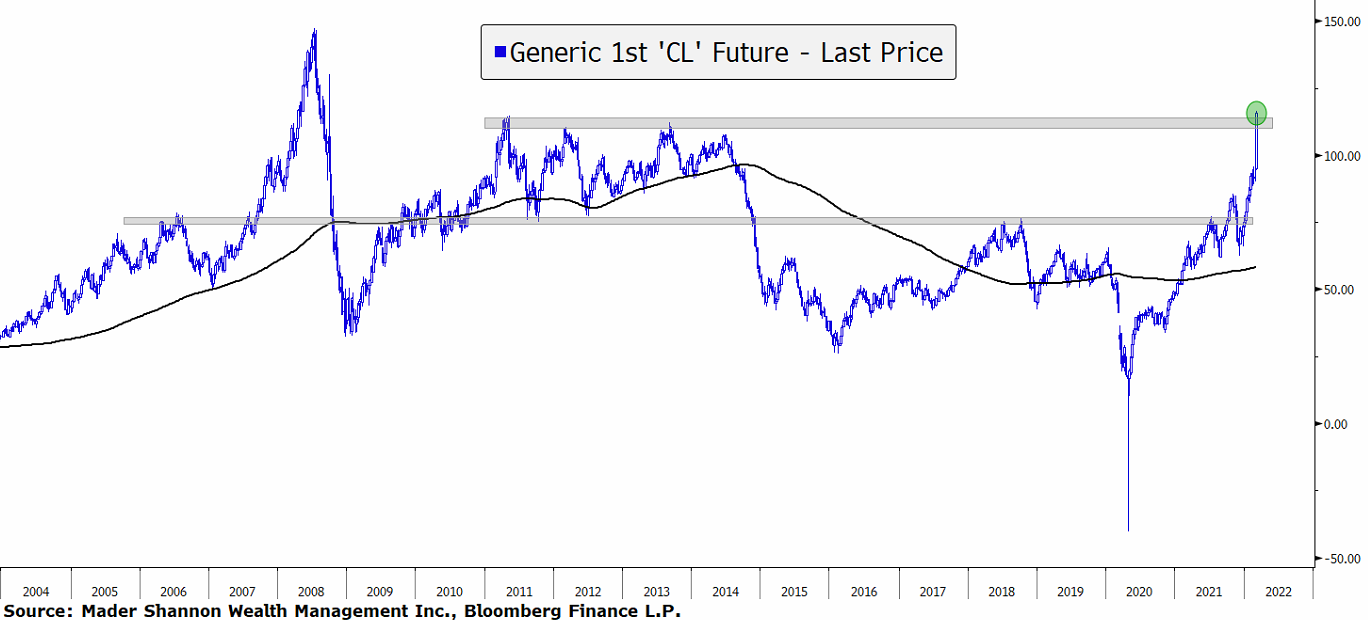

Energy prices are rising, too. Crude Oil jumped 26% last week, the most since 1983 excluding recessionary times, and the largest one-week increase ever on a dollar basis.

The rise in WTI Futures turned overhead supply from 2011-2013 into downside support. For oil bulls, the ‘08 high near $150 is the next area of resistance to watch.

Russia exports about 5 million barrels of oil per day, but those barrels are struggling to find a home in the current environment. Even though energy products have largely been spared from punitive sanctions thus far, a number of private companies have acted unilaterally to create a virtual blacklist for Russian oil cargoes. Shell Plc, one of the few companies to continue Russian operations, last week bought a cargo of crude at a $28.50 discount per barrel as compared to the Brent benchmark. But millions of barrels still have nowhere to go, and as long as the embargo holds, that means a shortage of oil supplies to the rest of the world.

At last week’s meeting, OPEC+ (of which Russia is a leading member) decided to maintain its plans to increase production at a rate of only 400,000 bpd per month, despite the Russia/Ukraine conflict and calls from outsiders to accelerate the pace. While a faster ramp-up in output could have alleviated some near-term supply pressures, industry experts are skeptical that OPEC and its affiliates can completely fill the gap. According to Pioneer Resources CEO Scott Sheffield on the company’s February 17th earnings conference call,

“OPEC and OPEC+ is going to run out of capacity by the end of 2022. And that’s even been stated by several OPEC and OPEC+ countries.”

It was, perhaps, a rather unrealistic expectation to expect OPEC+ would significantly increase production in the first place. While the Middle East had long been in the proverbial driver’s seat when it came to global oil production, sustained higher oil prices and technology improvements throughout the 2000s and early 2010s allowed North American producers to get a foot in the door. Oil production growth in North America was flat for the 15 years from 1995 to 2009, but growth since then has convincingly outpaced the global average.

True, it may not be fair to expect the rest of the world to match North American growth on a percentage basis when NA production was starting from a much lower base. But the phenomenon goes beyond percentages. Compare the cumulative growth in barrels per day. North America represents less than a quarter of global supply, yet since 2009 has added more capacity than the other 75% combined. In fact, according to the EIA’s most recent global production data, the rest of the world is actually producing less than it did a decade ago.

So if any region can be expected to increase production enough to meaningfully offset the potential loss of Russian exports, perhaps we should look to North America. A nuclear agreement that moderates sanctions on Iran could quickly unlock 1 million barrels per day or more, but that agreement is as uncertain as ever. There are no such restrictions on U.S. shale.

Except for the ones they’ve imposed on themselves.

After the 2014 oil collapse that crushed the domestic oil and gas industry, investors stopped rewarding companies that grew production quickly, and instead focused on those who returned stable and predictable cash flows to shareholders. In doing so, they instilled an unprecedented level of discipline into industry executives. Production since the pandemic has been slow to return, and less efficient oil rigs have remained offline.

But that was before the price of West Texas Intermediate had returned to $100. Surely that’s high enough to encourage more capital spending and faster growth, right? According to Mr. Sheffield, it’s not.

“Long term, we’re still net zero to 5% (annual production growth). It’s going to vary. We’re not going to change, as I said. At $100 oil, $150 oil, we’re not going to change our growth rate. We think it’s important to return cash back to the shareholders.

In regard to the industry, it’s been interesting watching some of the announcements. So far, the public independents are staying in line. I’m confident they will continue to stay in line. The private independents, a few of them, as we all know, are growing. They’ve announced growth rates in the 15% to 25% per year range… People that are growing at 15% to 20% are going to run out of inventory fairly quickly… A lot of the privates are experiencing labor issues, cost issues, can’t get equipment. So that’s going to prevent the rig ramp up.”

If he’s right, domestic supply could ramp up in the near-term thanks to private operators, but it can’t be sustained without additional resources. And public executives are still too fearful of investor backlash to go back on their promises to stay disciplined. It’s not an inspiring point of view.

If the world continues to abstain from Russian energy and the supply/demand mismatch persists, we may all need to buy a bicycle.

Nothing in this post or on this site is intended as a recommendation or an offer to buy or sell securities. Posts on Means to a Trend are meant for informational and entertainment purposes only. I or my affiliates may hold positions in securities mentioned in posts. Please see my Disclosure page for more information.

The post Oil’s Supply Problem first appeared on Grindstone Intelligence.