Second Quarter Recap – State of the Market

The second quarter of 2022 is in the books. Catch up on what you missed

Equities

Stocks are off to their worst start to a year since 1970. The tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite led to the downside both in the first half and in Q2. The Dow Jones Industrial Average, meanwhile, fell by only half as much in each period. Unsurprisingly, The Russell 3000 Value index has outperformed its Growth counterpart over that period, too. You can’t blame analyst earnings expectations for the weakness – blended 12-month forward earnings estimates for the S&P 500 are still rising. Instead, it’s investors’ confidence in those earnings estimates that’s driving declines. The forward price to earnings ratio of the S&P 500 has fallen from its 2020 high of 23x to less than 16x today.

Of course, this is nothing new. Consensus estimates rarely, if ever, correctly forecast downturns in earnings. Stock prices lead earnings, not the other way around. Still, it’s rare to see valuation ratios fall this quickly, especially outside of a recession.

Energy stocks avoided the selloff for most of the year. While the S&P 500 was 13% below its high on June 8th, its energy component was up a whopping 65% over the same period. In the weeks since, Energy has fallen more than 20%. Not even the strongest areas of the market can ignore a bear market forever.

Looking ahead, Energy bulls want prices to hold these 2018 highs. It’s a logical place to backtest, and as long as prices stay above that support zone and their rising 200-day moving average, the sector’s uptrend remains intact. Even after its recent correction, the group is still up 30% in 2022.

Small cap stocks are trying to hold a major support level that marked significant turning points in 2018 and 2020. With the group undoubtedly in a downtrend, we can’t assume that any support level will hold, but this is as good a place as any for a reversal. On the most recent test, momentum failed to reach oversold territory, creating a potential bullish momentum divergence.

Fixed Income

The bond market has been anything but boring of late. For one, U.S. bonds are off to their worst start in at least 50 years.

The place investors have historically gone for safety has provided nothing of the kind, with the index off more than 10% year-to-date. On an inflation-adjusted basis, the performance is even worse.

The rally in U.S. Treasury rates has brought the 10-year yield back to its December 2018 peak, which at that time was followed by a reversal in Federal Reserve policy, a bottom in stocks, and 18 months of rapidly rising bond prices. Price has memory. Last week, rates fell by the most amount since March 2020.

The action has been mirrored in Europe, with benchmark German yields jumping 200 bps in 2022, to an 8 year high of 1.9%. German 2-year yields had their largest trading range in history last week. In Italy, where government yields include a risk premium reflecting a relatively weaker fiscal position, bond price swings have been erratic, with yields moving as much as 40bps in a single day. After an unplanned weekend meeting in mid-June, the European Central Bank committed to exploring measures that would mitigate fragmentation, helping to stabilize the market.

Back home, higher risk bonds are under similar pressure. The interest rate spread between junk bonds and risk-free Treasuries has climbed from less than 2.2% a year ago – one of the lowest levels ever – to almost 6% today. Credit spreads rose 175 bps in June alone.

It’s not unusual for these types of tightening in credit conditions to precede recessions. At the very least, they tend to coincide with severe economic slowdowns.

Fed Up.date

The Federal Reserve started raising short-term interest rates with a 25bps hike in March. In May, they raised the benchmark overnight rate an additional 0.50%, and simultaneously announced plans to reduce the size of their balance sheet. It’s quite the shift from January, when market participants broadly expected between two and three 25 basis point hikes from the FOMC by year-end. Wall Street now expects the equivalent of thirteen such moves, in addition to QT.

The shift in forward guidance from Fed officials has been rapid, and in recent times, unpredictable. It’s led some market watchers to question the credibility of the world’s leading monetary authority. Consider this:

In their March 2021 Summary of Economic Projections, the bulk of the FOMC saw zero rate hikes until 2024, as demonstrated by the infamous dot plot. James Bullard, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, was the first to vocally deviate from that path – in June ’21, he predicted a rate liftoff in late 2022. Rafael Bostic, leader of the Atlanta Fed, agreed, and in November voiced the possibility of a second 2022 hike. By mid-February, Bullard and Bostic were talking about 4 hikes this year. Only a month later, 6 quarter point increases was the standard. And a month after that, Bullard voiced support for a 3.5% rate by year-end, the equivalent of more than a dozen hikes in calendar year 2022. By the May FOMC meeting, it seemed the furor had peaked with the decision to raise rates by a half percent. Jerome Powell, Chairman of the Federal Reserve, assured the market that 50 bps hikes were all that was needed and ruled out a hike of 75 bps or more at the upcoming June meeting. Then he raised rates by 75 bps in June anyway. The only warning was a May inflation reading that exceeded expectations, followed by a string of news reports in the days before the FOMC meeting signaling that 75 bps was on the table. It’s no wonder the credibility of forward guidance from the Fed is in question these days.

For now, the market is pricing an additional 75 bps increase to the federal funds rate at the July 27 meeting and 3.25%-3.50% by year end. Compared to the near-zero rates we’ve grown accustomed to over the last 15 years, 3.5% seems high. But that’s still well below where short-term interest rates were prior to the 2008 financial crisis

The Fed’s balance sheet won’t come anywhere close to 2008 levels either. It may not even reach pre-pandemic levels. Rolloff started in June at the pace of $47.5 billion per month ($30 billion in Treasury securities and $17.5 billion in agency debt and mortgage-backed securities). The amount will rise to $95B per month in September, and continue until the balance sheet reaches the minimum level needed to provide ample market liquidity. The wrinkle is, no one knows what that level will turn out to be. The Fed’s only previous experience with balance sheet reduction was in 2017-2019, when the monthly rolloff caps were lower, and the process was supposed to be ‘as boring as watching paint dry.’ In that episode, the Fed overshot its mark, forcing it to engage in reserve management operations to restore ample liquidity to the overnight lending markets. Only months later, pandemic turmoil caused them to initiate the largest round of quantitative easing in history.

Expect the Fed to be more cautious this time around by slowing the monthly balance sheet reduction well in advance of reaching their estimate of the appropriate end level.

Commodities

Commodities were one of the few places investors could hide in the early part of the year, but the bloom came off the rose in the second quarter. A number of developments are to blame, but fears of a global recession sit near the top of the list. China continues to grapple with the pandemic and remains committed to a COVID-zero policy that prescribes broad lockdowns to quell outbreaks. That policy, forcefully defended by President Xi again last week, has pressured economic activity in the region even after restrictions were loosened in early June. European economies are suffering from the consequences of Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine. The disruption of trade and increased uncertainty has weighed on sentiment and slowed the region’s recovery from the pandemic. And here in the United States, economist’s estimates of recession odds are on the rise amid the Fed’s tightening regime. As a result, the metal with a PhD in economics has fallen to the lowest level in over a year.

Dr. Copper’s track record as an economic forecaster is not perfect, but then again, neither is anyone else’s. It pays to listen when he speaks.

The commodity weakness hasn’t been limited to copper. The CRB Raw Industrials Index as a whole is rolling over.

This is a chart I highlighted at the beginning of the year as one to keep an eye on. Prices are now below the highs they set back in 2011. The bulk of the CRB is energy, so for clues about the direction of the index, we should probably be watching its largest component: crude oil.

After bottoming in April 2020, WTI surged steadily higher, culminating with a blowoff rally to nearly $140 per barrel shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. That was the highest level since the all-time highs set in 2008. In the months since, oil has settled in a range near the top end of the 2010-2014 trading range. No matter how you view it, WTI is not in a downtrend. Prices are still setting higher lows and are comfortably above a rising 200-day moving average. For them to reach new highs, though, they may need more time to digest these long-term resistance levels.

The first sign that bears may have the upper hand would be a break below the uptrend line that connects the recent string of lower lows. Trendline breaks aren’t as important as breaks of horizontal resistance, but a trend can’t change without first breaking a trendline. (I once heard that trendlines should be drawn with crayon, not pencil, and I’ve thought of them that way every since. They’re not absolute, and they can be drawn through a dozen different points, so a break needs to be clear and convincing.)

Another breakout or a reversal will have major repercussions. Crude oil is probably the most important commodity in the world today. It’s certainly the most important in the eyes of most of the public, as Americans are paying more at the pump than we ever have before. The average price for a gallon of gas in the United States reached $5.35 at the end of June, compared to $2.19 during the pandemic lows in 2020.

It’s a multi-faceted problem on the supply side. Domestic oil production has yet to recover from the losses sustained during the pandemic, when oil prices reached negative $47 per barrel. After the last 10 years, it’s not hard to understand why. When crude collapsed in the fall of 2014 and drove the industry to the brink of bankruptcy, the shale producers that survived were pressured by investors to tighten their belts and target disciplined growth. Some listened. The ones that didn’t were punished when 2020 arrived. Gone are the days of expanding production at all costs. Industry executives focus now on ‘sustainable growth’, ensuring that supplies don’t overwhelm demand, so cash flows can remain positive and support returns to investors. No one wants to risk ramping investment into another oil price drop.

In a normal environment, international production might offset the domestic supply shortfall. But Russian oil is anathema in the Western world, and the rest of OPEC+ has failed to pick up the slack. Political unrest in Libya prompted the state oil company to temporarily suspend shipments from two of its three largest ports. In Ecuador, production has been hampered by weeks of protests. OPEC production in May was lower than April, despite the cartel raising its daily production target for the month.

Aramco, Saudi Arabia’s state-owned oil conglomerate, has claimed it can pump an additional 1 million barrels per day for a total of 12 million b/d. That would certainly help to alleviate the oil shortage. But they’ve never done so before, and industry experts are skeptical the oil giant can do so on a sustainable basis.

The supply problems in energy extend downstream. Refining capacity in the United States has fallen from 19 million barrels per day to less than 18 million since 2020. Low energy prices during the pandemic accelerated plans to retire existing plants or convert them to renewable diesel facilities, and a Louisiana refinery closed after damage from Hurricane Ida. New capacity additions are unlikely, even with gas prices at all time highs. It can take a decade to bring a new refinery online (helping explain why we haven’t built a new one in the United States since the 1970s), and it can take another decade or more before getting a return on the initial investment. With world leaders pushing for an end to the sale of gasoline-powered cars by 2035, a 20+ year investment is a risky proposition. Any near-term correction in the energy shortage will likely have to come from the demand side.

Everything Else

The US Dollar Index has broken above previous highs set in 2016 and 2020. With the Fed raising interest rates more quickly than other developed markets, and Europe embroiled in geopolitical strife, the United States offers a relatively more attractive market for investment (despite this year’s poor performance). That’s pushed the U.S. Dollar close to parity with the Euro – which hasn’t been seen in 20 years – and pushed the Japanese Yen to its weakest level since 1998. The increase over the last year has been a headwind to earning of U.S. companies – whose export customers face a loss of purchasing power, and whose foreign earnings are reported in USD.

Crypto markets found no reprieve in the second quarter. Bitcoin is now 70% below its all-time high set in November of last year, and fell 40% in June alone. Cryptos were often hailed as a new safe-haven, an asset class uncorrelated with equities that offered differentiated and spectacular returns. Returns in the space have been spectacular at times, to be sure. But for now, it looks more like a levered bet on the Nasdaq. The trend in Bitcoin, and most crypto investments, is down until proven otherwise.

Macro Monitor

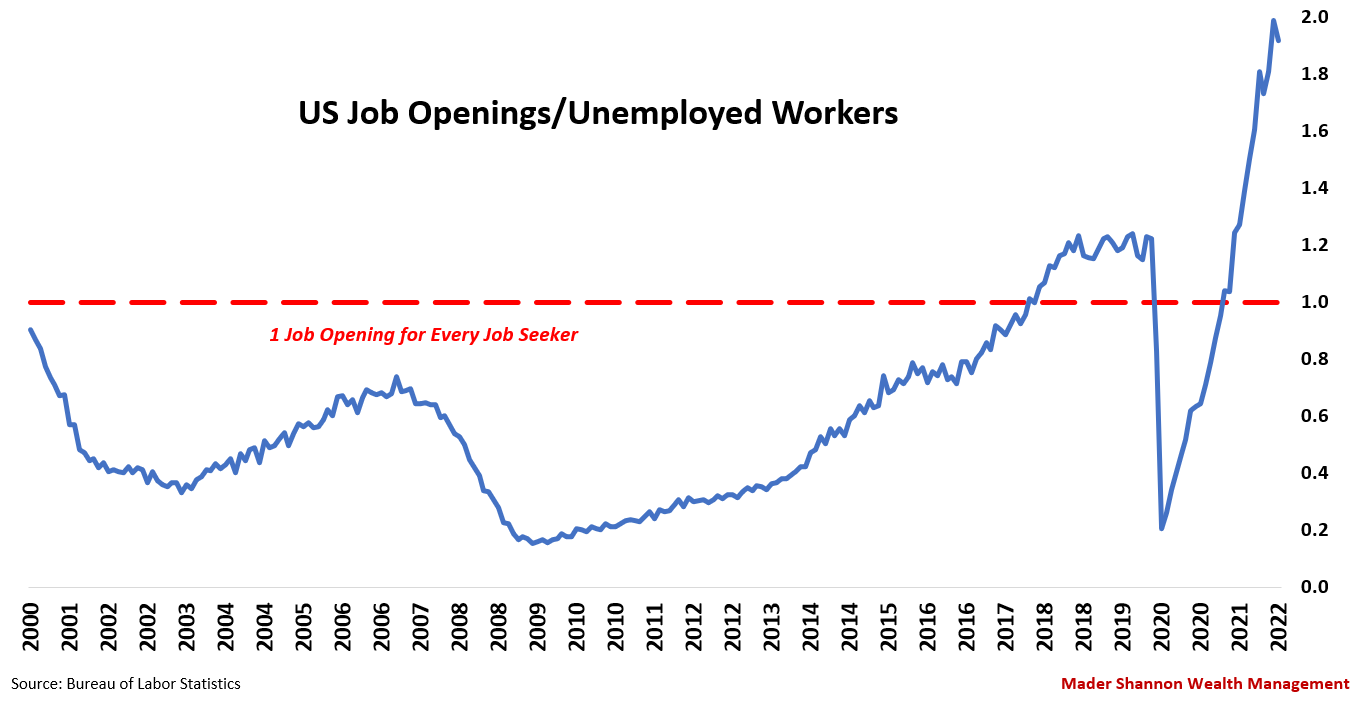

Despite all the talk about recession, the jobs market still says there’s nothing to be worried about. The U.S. unemployment rate is hovering near historic lows at 3.6%. You don’t have recessions without a rising unemployment rate, and unemployment can’t increase without increasing jobless claims. In the past, the weekly estimate of continuing jobless claims released by the Department of Labor has bottomed several months before the onset of a recession. Yet continuing claims hit a new low only 1 month ago, at the end of May and have risen only marginally. Initial jobless claims, though, seem to have troughed in March. We’ll see what this week’s payrolls report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics says about the labor market. But even if payrolls decline, it won’t be from a lack of demand for workers – there’s still 1.9 job postings for every unemployed person in America.

Here’s everything you might have missed from Means to a Trend in Q2

Bullish Momentum Divergences vs. a Bear Market

Searching for Stabilization Amid a Volatile Market

First Quarter Recap – State of the Market

Nothing in this post or on this site is intended as a recommendation or an offer to buy or sell securities. Posts on Means to a Trend are meant for informational and entertainment purposes only. I or my affiliates may hold positions in securities mentioned in posts. Please see my Disclosure page for more information.

The post Second Quarter Recap – State of the Market first appeared on Grindstone Intelligence.