Mid-Month Macro Musings

Is it time to start worrying about consumer debt levels?

In the 10 years leading up to the pandemic, US GDP annualized at about a 2.5% growth rate. That’s a significant step below average growth in the decades leading up to the turn of the century, where productivity gains and strong population growth helped GDP grow by well over 3% per year.

If you ask most mainstream economists - including those at the Federal Reserve, the IMF, and the OECD - they’ll tell you the US economy is most likely to grow at a rate of about 2% over the next decade.

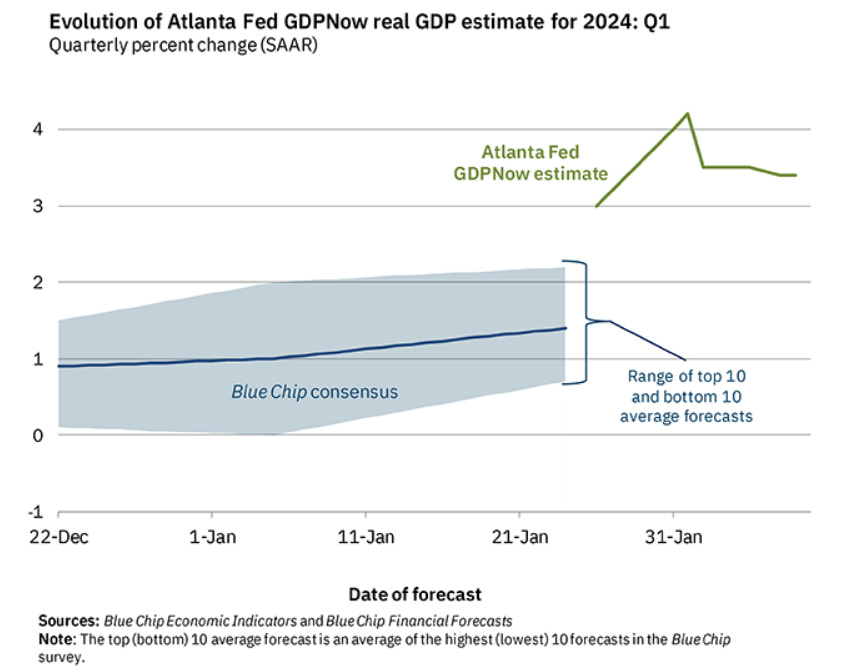

But the US economy keeps outperforming expectations. GDP grew at a 4.9% rate in Q3 2023 and 3.3% in Q4, despite overwhelming predictions for a downturn. And if recent data is any indication, the first quarter of 2024 will be just as healthy. The Atlanta Fed GDPNow real GDP estimate for Q1 is at 3.4%, more than double the Blue Chip consensus estimate.

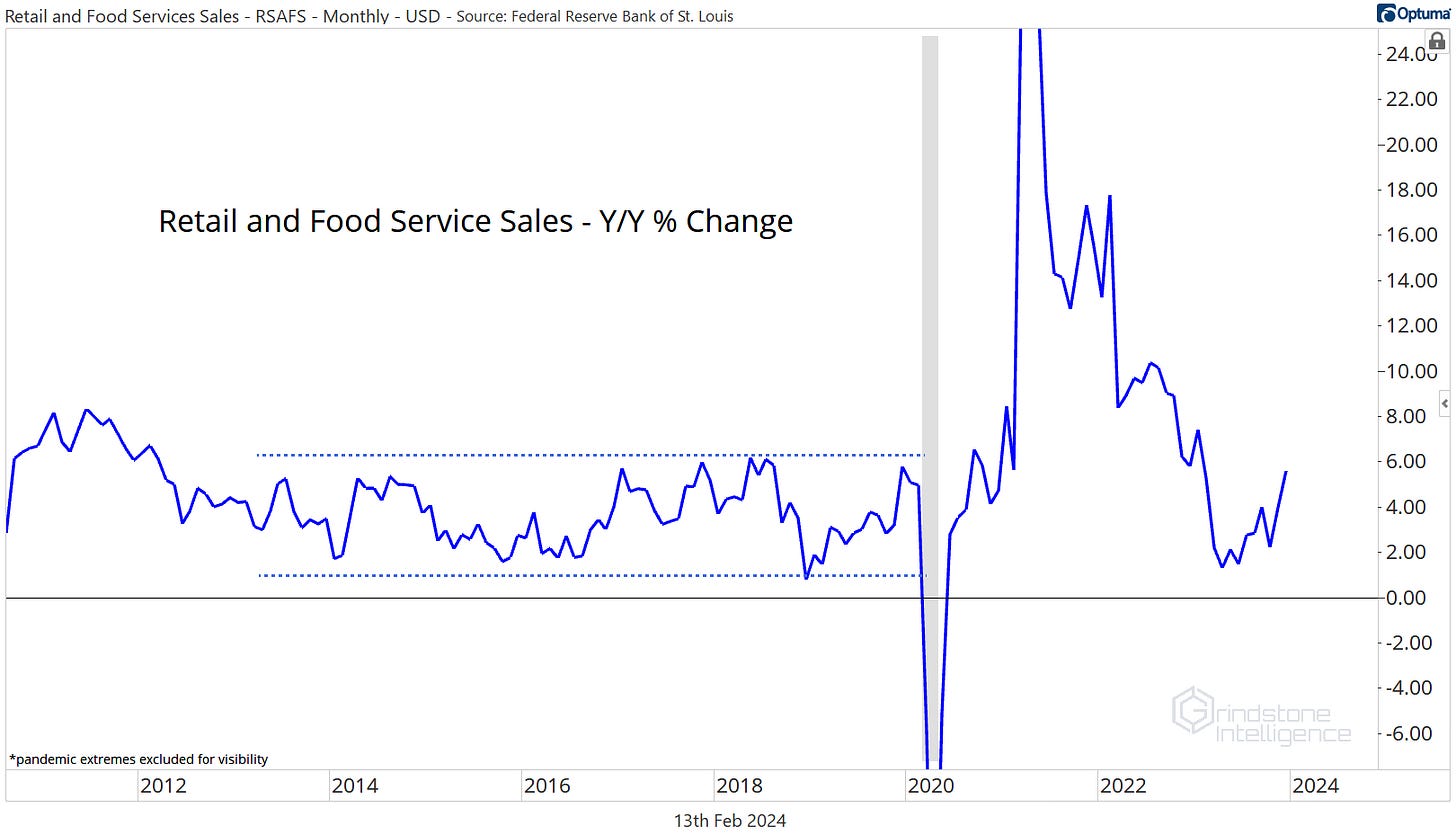

We have strong consumer spending to thank for the resiliency. Consumption accounts for about two-thirds of the US economy, and retail sales in December rose to nearly 6% - the highest since last February, and near the high end of where retail sales oscillated between 2013-2019. Adjusted for inflation, December’s print was the best since February 2022, when consumers were still riding high from pandemic-era stimulus checks.

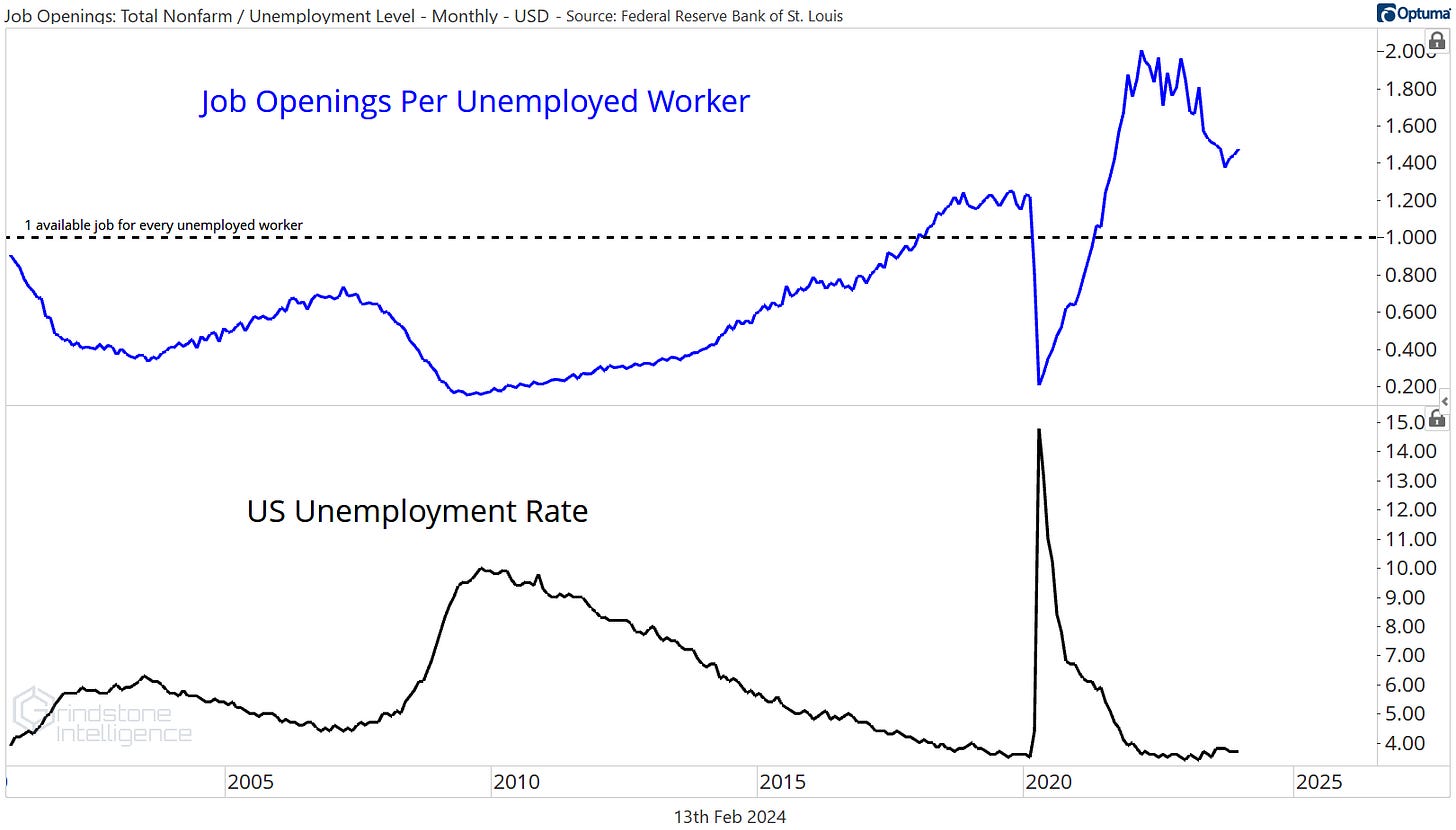

The strong consumer is fueled in large part by a strong labor market. Yes, job cut announcements have dominated the newswires (though cuts in January still came in lower than they did the prior year), but the unemployment rate is hanging near 50-year lows at 3.7%, and there are 1.47 job openings out there for every unemployed worker in the labor market. For context, from the start of the data set until the onset of the pandemic lockdowns, the ratio of job openings to jobless never climbed above the 1.25 print set in the ultra-tight labor market of 2019. By this measure, the labor market is 20% tighter than it was back then.

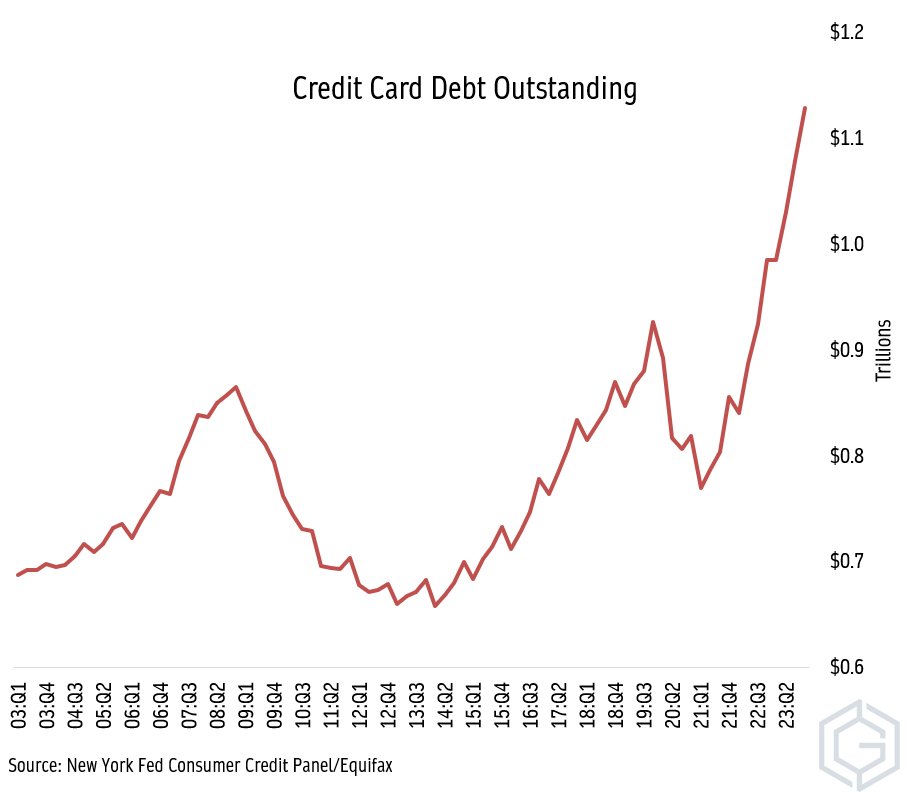

It’s not just the strong labor market, though. The US spending spree is also being fueled by a surge in borrowing. According to the New York Fed’s Household Debt and Credit report, credit card debt surged to more than $1.1 trillion dollars in Q4.

Should that have us worried?

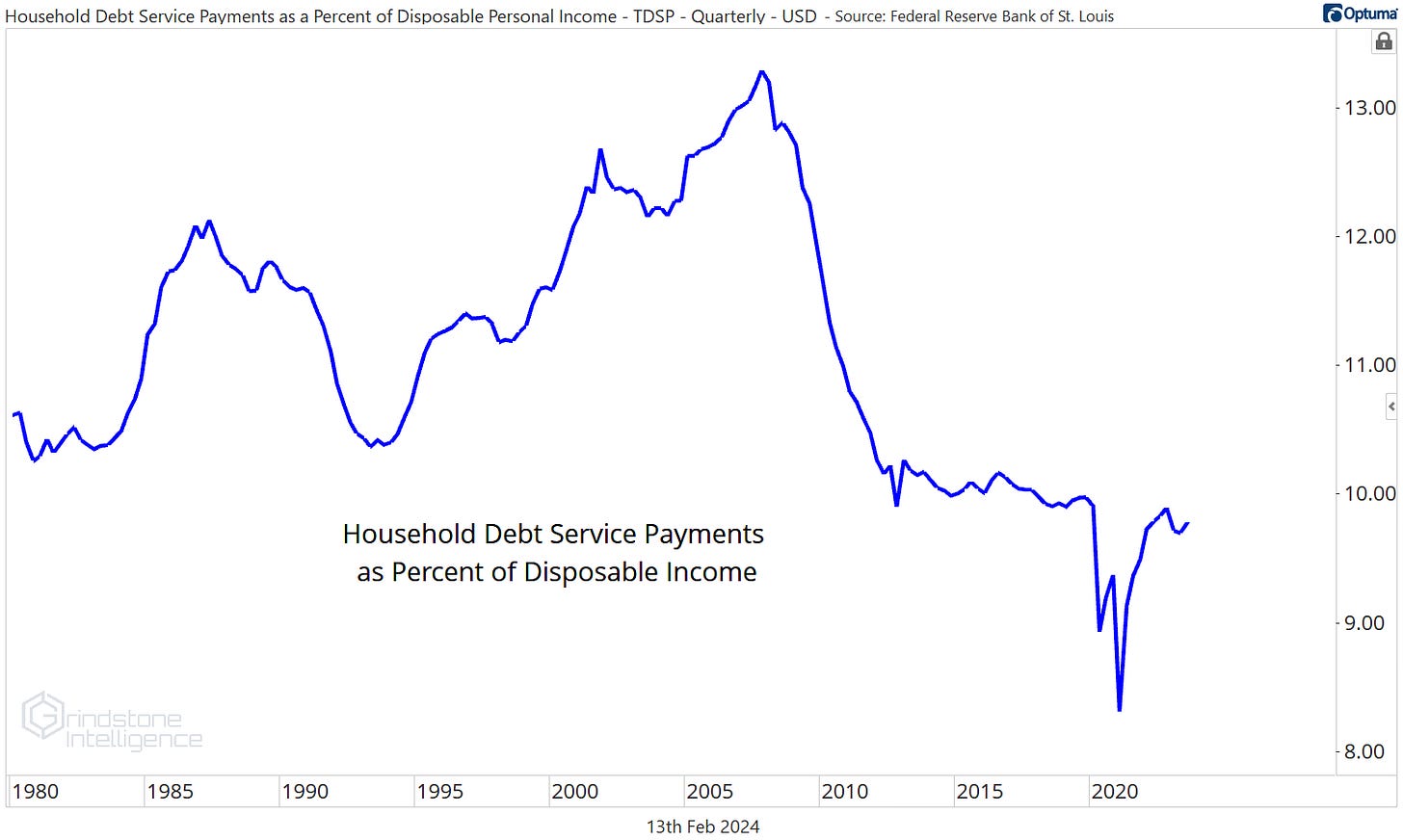

It’s not hard to find someone that will tell you these debt levels are unsustainable. Dave Ramsey probably has a stroke every time he thinks about it. After all, this is one TRILLION Dollars! But debt levels only become a widespread problem when people can’t pay their bills. And thanks to rising incomes, debt is more manageable than it was in the 40 years prior to 2020. Household debt service payments as a percent of disposable income were still below 10% in the third quarter.

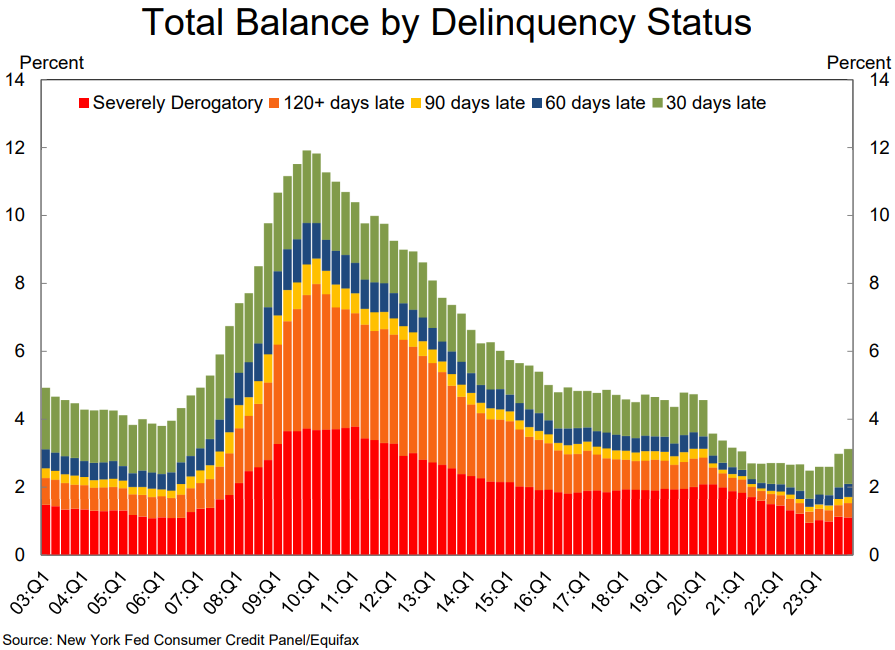

So, at least on the surface, these levels of debt aren’t a problem. Check out the delinquency status of all borrowings, including credit cards, auto loans, and mortgages. The percentage of balances that are in some stage of delinquency is only about half of what it was pre-COVID.

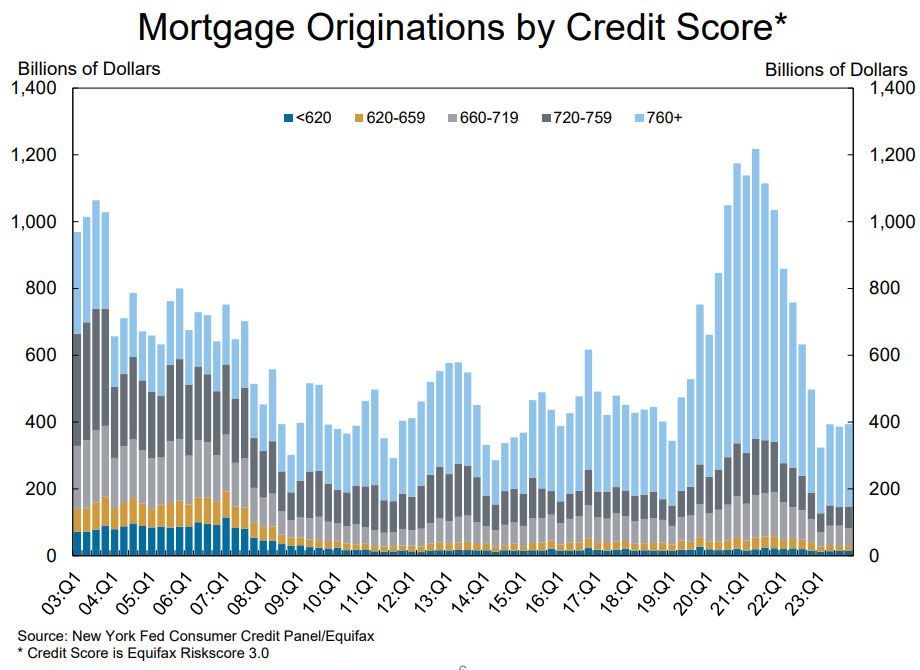

Just as there are layers to the stock market, though, there are layers to the US economy. We can’t hope to adequately describe credit conditions with a single chart. Some context on the total delinquencies number is important. Ultra-low interest rates in 2020 and 2021 prompted millions of Americans to either buy a home or refinance their mortgage. Mortgage originations more than doubled from 2019 to 2021.

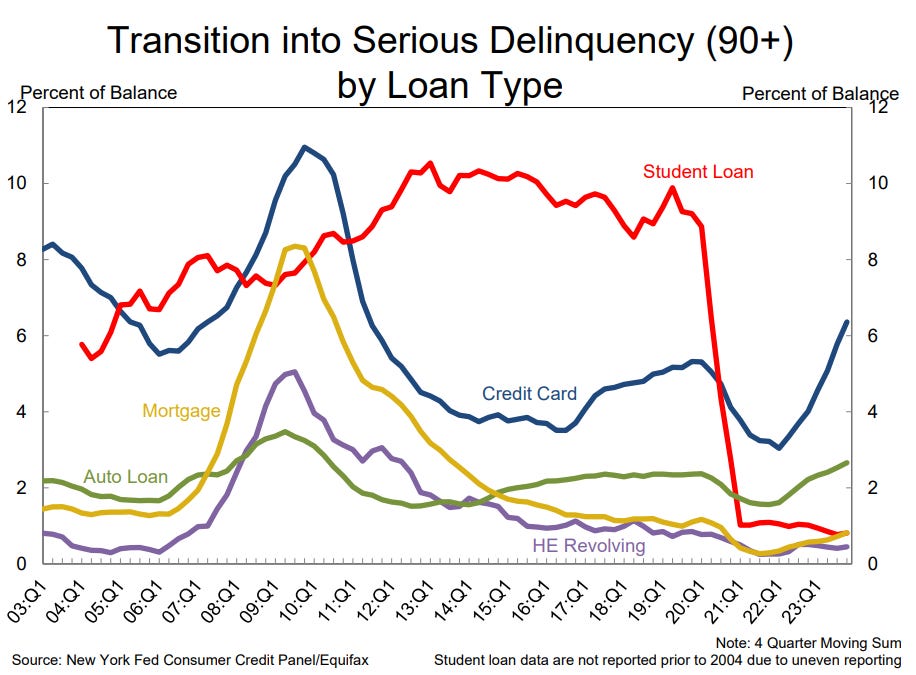

Low interest rates have made servicing mortgage debt easier than it’s been in decades. Mortgage and HELOC delinquency rates today are significantly better than they were from 2000 to 2019. And since mortgages make up a whopping 68% of total US consumer loans, low mortgage delinquencies are holding down low total delinquencies.

That strength masks growing weaknesses elsewhere. Credit card and auto loan delinquencies just hit their highest levels in more than 10 years.

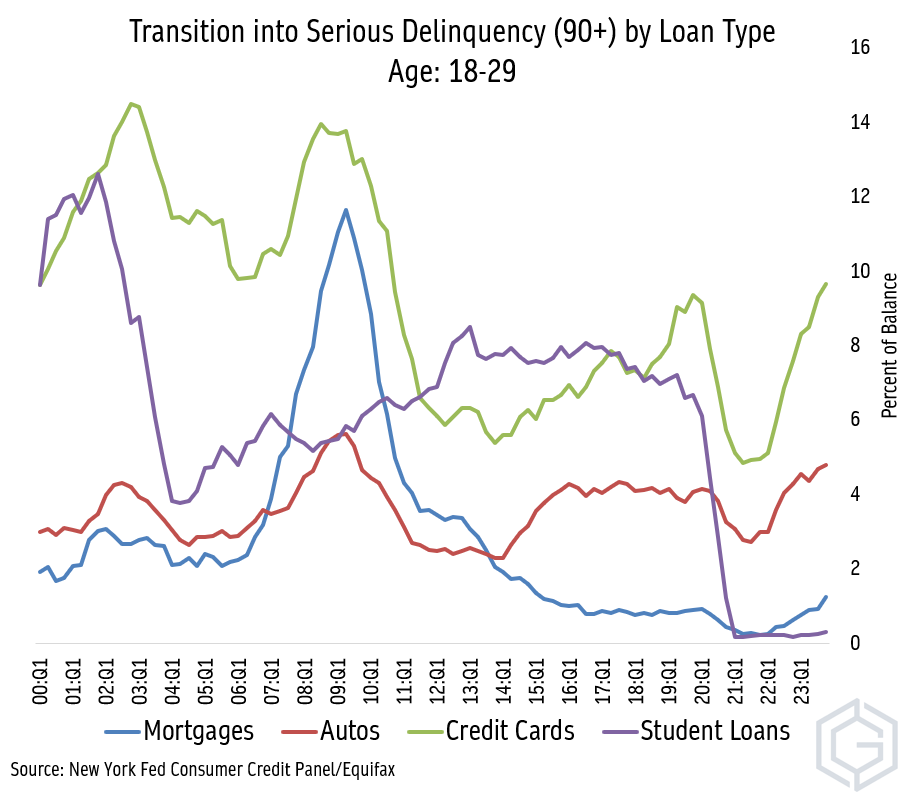

The younger the borrower, the worse things are. For 18-29 year-olds, delinquencies are setting new incremental highs for credit cards, auto loans, and mortgages. That’s before we’ve even felt the full weight of student loan payment resumptions.

At some point, those weakening credit metrics will become a problem. For this younger cohort, it might mean delaying household formation and/or putting off saving for the future. Both of those would weigh on long-term economic growth.

Near-term, though, the younger generation is a bit less important. Consumers over the age of 30 make up the vast majority of spending in the US economy, and since homeownership rates rise with age, that’s also the demographic benefitting the most from low mortgage rates. Even if young people have to start cutting back on discretionary spending, economic activity can continue to churn higher. We may not be saying the same if this weakness becomes more widespread.

S&P 500 Earnings

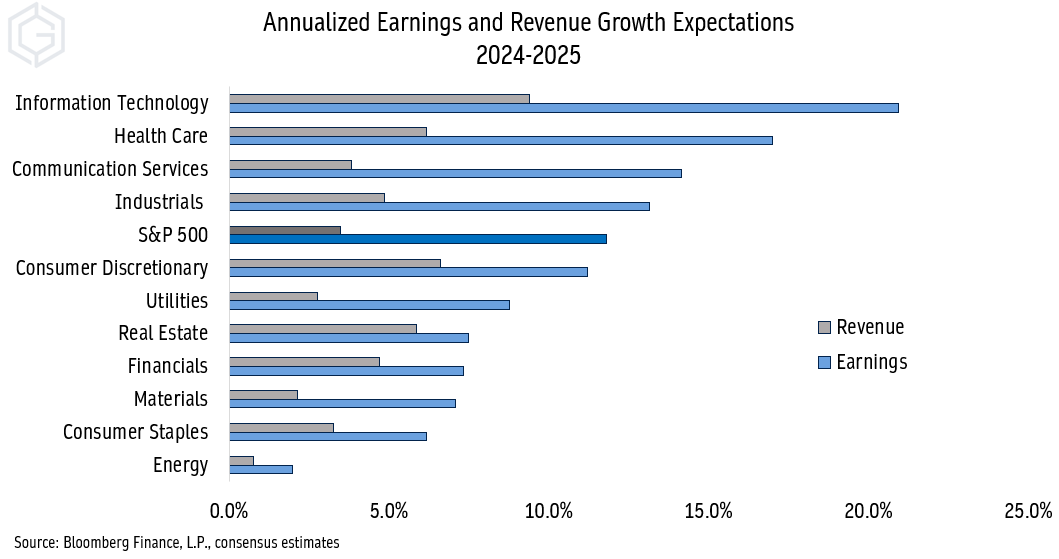

We’re nearing the end of the Q4 2023 reporting season, but everyone is already looking ahead to where earnings will end up in Q4 2024. After a year in which earnings growth was largely flat - and may even end up in negative territory - S&P 500 profits are expected to grow about 12% in 2024.

Major rebounds for earnings in the Information Technology, Health Care, Communication Services, and Industrials sectors are driving the above-average growth estimate.

Growth in 2025 is expected to be nearly as strong. If bottom-up consensus estimates are to be believed, earnings for the S&P 500 will rebound at an annualized rate of 11.8% over the next 24 months. We’re led by some familiar names: 21% growth per year from the Tech sector, 17% from Health Care, and 14% from Communication Services.

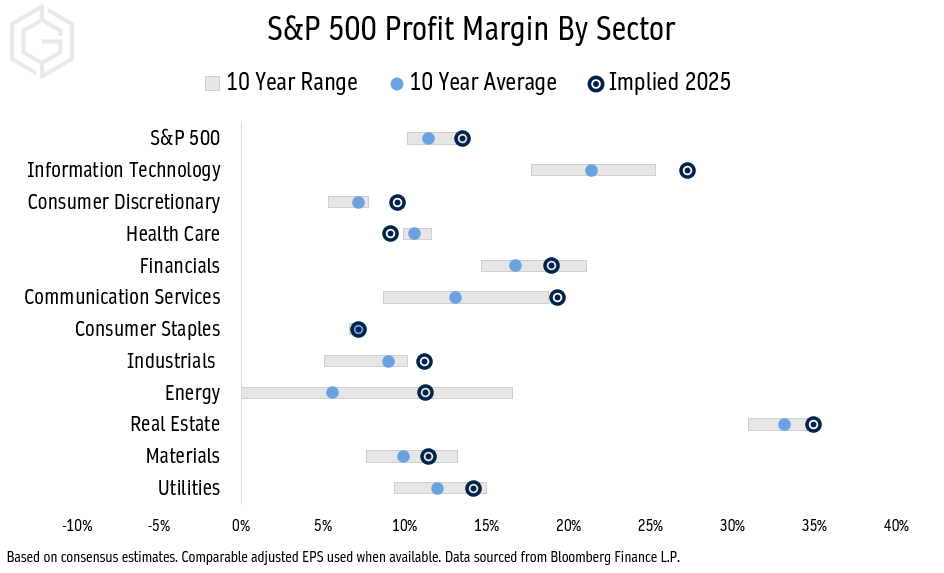

The trouble is, revenues are expected to grow at just 3.5%. That means the bulk of earnings growth must come from margin expansion - and margins are already at high levels.

It’s not that the projected growth in margins is unprecedented. But in the past decade, it’s taken significant changes like tax reform (2018) or a recession rebound (including the unwind of loan loss provisions by the banks in 2021) to see the type of improvement analysts are expecting as a matter of course over the next 24 months.

Earnings and revenue estimates imply that profit margins will hit new highs in 5 of the 11 sectors - 6 if you exclude the aforementioned 2021 outlier for the Financials. All but the Health Care sector are expected to turn in margins that are better than the 10 year average.

Maybe these growth estimates are achievable, but Wall Street analysts have a well-established reputation for being too optimistic about the future.

Consider us a skeptic. Barring a major shift in economic growth expectations, something closer to the long-term average earnings growth rate of 7% seems more realistic.